Think small and look for the singular delights in the big cities you visit, writes Lance Richardson.

Cities often strike me as the strangest places in travel, and they're strange for the simple reason that so many people live in them. Consider how complicated one person is, then multiply that by a million, or five million, or, in the case of Sao Paulo, 11.32 million. The true modern miracle is that our cities absorb a seemingly endless number of idiosyncrasies and still work. The garbage gets removed. Lights come on at night. The coffee is freshly ground and workers line up to buy it with a minimum of fuss or murderous outbursts. There are always exceptions - Caracas, Guatemala City, Luanda - but most cities manage to hold it together despite the odds.

Then there is the sheer variety, which is also incredible. The law of averages says something with so many ingredients should balance out to a bland muddle; mix a bunch of colours together and you end up with brown. But cities seem to refute this law by being unique and occasionally dazzling.

There are steamy cities, prim cities and completely neutered ones: compare Rio de Janeiro to bleak Pyongyang in North Korea, where nothing is allowed unless you are Dear Leader. There are noir, paradoxical cities like Los Angeles, both a fabled dream factory or a corpse decaying in the sunshine. There are dystopias like Shenzhen, often compared to the future inferno of the movie Blade Runner; and dubious oil "utopias" like Dubai. There are cities that obsess over their own good fortune to be gorgeous , and others that are resigned to ugliness but have a great time of it anyway .

Georges-Eugene Haussmann steamrolled the mediaeval tangle of central Paris to create grand boulevards in the 1860s: this is the planned city, where beauty comes at the cost of natural spontaneity. Mumbai, by contrast, is a city of spontaneous slums, Johannesburg of electric fences and Sarajevo of old bullet holes. Cairo stands for ancient artifacts, road rage and revolutions. There are cities of bones, such as Mexico City, where Aztec temples lie buried beneath the central main plaza, Zocalo, and a lopsided cathedral. There are cities crumbling to modern ruins, like Detroit, which recently declared bankruptcy and may auction off its art holdings to feed the wolves of Wall Street.

London, for its part, is a city of ghosts: "the ghost of empire, or the blitz, the plague, the smoky ghost of the Great Fire," wrote A.A. Gill in a recent profile of the capital. "London can see the dead and hugs them close."

New York strikes me as the polar opposite of this - a city that ignores its ghosts, climbing over history in the pursuit of new promise, greater profits and eternal youth.

The author Kurt Vonnegut once called New York "skyscraper national park". The title is apt: national parks are wild places, full of hidden pitfalls and capricious animals.

Still, for all their variety, cities evoke a fairly binary reaction in travellers. You are either a city person or you are not. A city on the itinerary is something to celebrate, or it is something to be endured on the way to greener pastures.

The Welsh travel writer Jan Morris leads the pack of admirers. "For me an element of hope is the essence of cityness," she writes in her book on Trieste, Italy. "When I see a city in the distance, out of the open country, I always get a move on myself. The more isolated the city, the more hopeful, because then it offers a more spectacular contrast to the bucolic world outside."

Paul Theroux has the opposite view, however. When I interviewed him recently about Africa, he described the bush as the true site of hopefulness. "There's something unsustainable - unknowable - about city life," he told me. "I don't denigrate it, but the urbanisation of the world is to me a bad thing."

But perhaps the most influential naysayer of cities is actually Georg Simmel, whose 1903 essay The Metropolis and Mental Life offers a litany of complaints. Cities, he wrote, are so full of stimulation that trying to absorb it all would induce a total mental breakdown. In order to prevent this, a city-dweller "creates a protective organ", or blase outlook, where relations with others are governed by "a relentless matter-of-factness". What Simmel means here can be thought of as the infamous urban reserve - New York attitude, Parisian haughtiness. He argues that being aloof in a city offers a measure of protection against information overload. But the endpoint is isolation: city people are physically close but all alone in a faceless crowd of strangers.

Is Simmel right? Is Morris right? Or are they actually both right? It seems to me that a city can be simultaneously hopeful and overwhelming, thrilling and lonely. In fact, the combination of these elements is what lends a city its singular character and tempo. Some cities are big country towns with modest ambitions. Others are anonymous hives, where brazen fashionistas weave through a population that is content with nothing less than everything.

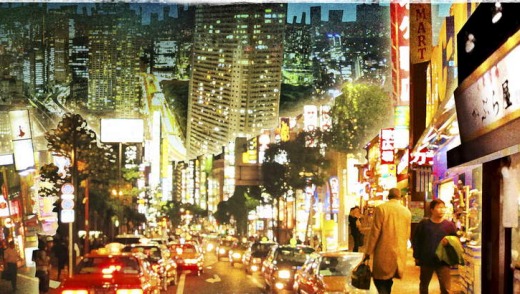

Tokyo is the ultimate case study of the current era, taking Morris and Simmel to logical extremes while sending travellers down a surreal rabbit hole. Once a quiet seaside village, greater Tokyo is now the most populous metropolitan area in the world. In the opening scene of the 2003 film Lost in Translation, Bill Murray, sliding through the district of Shinjuku in a black cab, stares out the window and rubs his eyes in disbelief. It is an appropriate reaction: Tokyo is an incandescent spectacle.

On one hand it represents the most thrilling urban experience on the planet. Visit Tokyo and you can pretty much find anything ever imagined, from exquisite French cuisine to "cat cafes" - buy a coffee, pat a kitten - and inner-ear massages. In parts of Tokyo, like Shibuya, neon lights have banished the night time. But who needs sleep when there are things to see, exotic dishes to taste? You can be anything you want here: a Harajuku girl, a tech-head in Akihabara, a fake-tan "mamba". Here the urban reserve translates, for travellers, into a kind of liberation. There's no better place to embrace your fantasies and then kick back to watch the tide of humanity rush past. If travelling is a type of voyeurism, Tokyo is the peep show par excellence.

I recently spent a week in the city, romanced by the dazzling strangeness of it all. But I was also unsettled by the labyrinthine density, which left me feeling claustrophobic in crowds so large they had their own current.

One evening in Shibuya, I was eating sushi with a local acquaintance. Since I was curious about Fukushima, I asked her what the mood had been in Tokyo at the time of the nuclear accident in 2011. She said people had reacted with calmness bordering on indifference. "Everybody went to work," she said. She went to work, too - she lives alone and "maybe it was just easier to be around others". But she also remembers wondering what would happen if radiation started to drift towards the city. Would they evacuate children on the bullet trains? What about her? Was she too old (at 33)? Would she get out? Does the city have emergency plans that cover the entire population?

"Probably not," she said. Tokyo sustains 13.23 million people. It is a city of stimulation, excitement, hopefulness; but in different circumstances its astonishing scope is also its undoing.

This sobering thought made me realise another thing about cities, which is that they're livable because we almost never consider their full complexity. Trying to hold all of Toyko in a single thought is counterintuitive; during a catastrophe it is terrifying. There are limits to imagination and modern cities exceed them. Think of New York and you're likely to picture the island of Manhattan, or perhaps just Central Park. Sydney, in my mind, is a small leafy patch of Surry Hills, with Circular Quay and Bondi Beach revolving around the outer edges.

A city could be infinite and we would still carve out digestible pieces and leave the rest untouched.

This is how I dealt with the sprawl of Tokyo - by focusing down on the backstreets of Nishiazabu, where restaurants are marked by warmly lit windows. I found solace in the lush garden of the Nezu Museum and walked across a highway to see the subterranean womb of the Musee Tomo and then chose to wander through obelisks in the elegant cemetery of Aoyama. And while I witnessed the blinding lights of Shinjuku, I slipped away afterwards, sleeping in less frenetic neighbourhoods filled with shrines and modest bathhouses. Tokyo became about small things: the quiet places.

This is the secret to travelling in big cities anywhere.

Are you a city person when travelling? What are your tips for travelling in cities? Post your stories and comments below.