A captivating landscape in Zimbabwe

Lying just south of Bulawayo, Zimbabwe’s second largest city, is one of the country’s most important spiritual heartlands. The Matopos or Matobo Hills is a sacred landscape of broken granite. Its rounded hills and boulders have withstood the rigours of time, beaten down by endless cycles of sun and rain.

The smooth domes of granite stand out like the backs of swimming whales or the heads of balding men, the latter being the one of the explanations of the origin for the name Matobo. The harsh solid rock surfaces support few plants, other than a variety of lichens whose vivid colours look like the paint splatters of some ancient children’s playroom. In the cracks and pools other hardy species have evolved to survive on the limited water available. There is the apparently dead Resurrection Plant that comes “back to life” with the rains, while several species live short lives in the temporary pools that fill after each storm.

Then there are the valleys and broken boulder-strewn hills where many plants and animals have found a niche, dependent on the water held in the underground cracks in the rock. Here you will find the Paper-bark trees, the Wooden Banana and many others. Look out for the covens of dassie, that diminutive relative of its nearest and much larger relative the elephant. The clicking of hooves is the sounding of the small klipspringer making off over boulders and slopes that we would find impossible to walk upon.

Matobo Hills

This rugged landscape receives better rainfall than the surrounding areas. As a result it can sustain a diversity of plants and animals. Several of the plants are unique to these hills, a testament of long-term evolution. It also supports many bird and animal species. The density of leopard and black eagle are thought to be some of the highest anywhere. The Matobo is one of the last Zimbabwean hot spots for rhinoceros, both black and white. Rhino tours where experienced guides are able to walk their guests towards these hefty beasts are one of the popular activities of the national park.

But it is not just in nature that is the uniqueness of the Matobo. Its spiritual power still captivates human interest. These hills have for millennia been home to people who have left visible traces as well as an intangible aura that is hard to explain. The hills have a pervading feeling of ancientness, human happiness and sadness, good and bad, military conflict and peace.

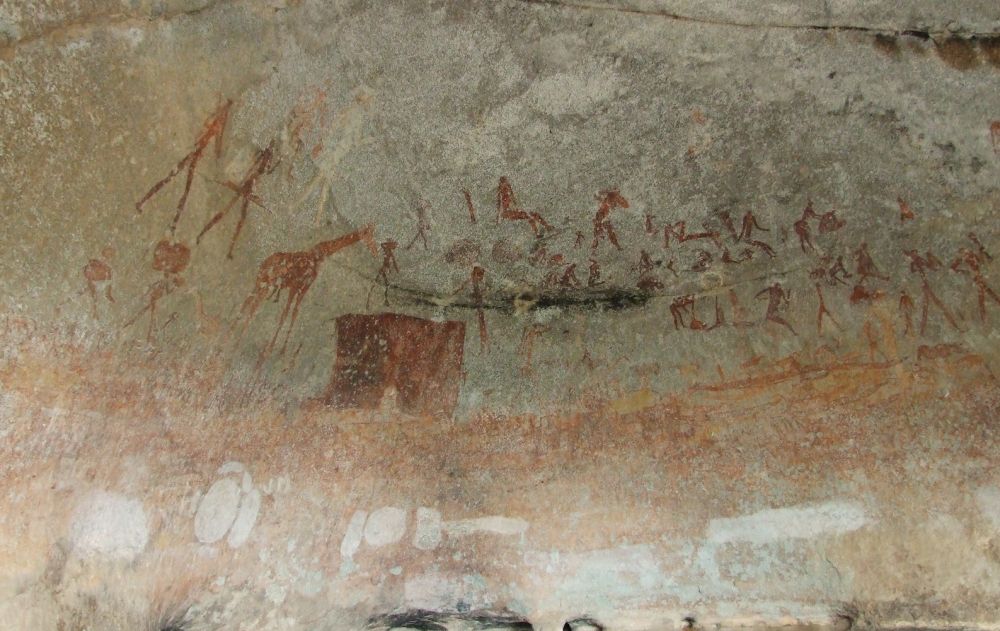

It is certainly no co-incidence that these hills have one of the greatest concentrations of rock art in the region. The hunter-gatherer peoples who once found security and sustenance in these hills have left countless paintings across the Matobo. Some are massive painted caves with hundreds of depictions of humans, animals and mystical forms. Most however are small scatters or isolated depictions on the under surface of overhanging rocks.

The art is not simplistic illustrations of their lives. There is a selection of what they chose to paint and not to paint. These are symbols and illustrations of their deepest religious feelings and understanding of the reality of life around them. They would relate to the viewer the complexity of social relations (age, gender and living in community) as well as the complex realm of spirits. This only worked for those brought up in their society, knowing the symbolism. We outsiders stand here not fully understanding this ancient and now largely forgotten symbolic language.

Matobo Rock Art

Popular painted sites that are open to visitors include White Rhino Shelter with its unique red outlined style. Try also to get to see Nswatugi Cave where the realistic giraffe paintings are some of the best such depictions in the hills. Unboundedly they are the work of a great and now forgotten artist. Bambata Cave is also well worth a visit. The walk there takes one through the varied natural environments that are the Matopos – streams, grassy areas, forests and the dry rocky surfaces of the hills. There are countless other painted sites and guests staying at some of the private facilities may be able to see some of these that are not open to the general public.

About 2,000 years ago farming came to the hills. In fact most of the Matobo World Heritage area is still farmed by small-scale farmers in the Communal Lands that surround the core area that is the Rhodes Matopos National Park. It is sad that most visitors don’t see this the real Matobo. It is the living Matobo with its homesteads and fields, with ceremonies and people. In fact it was on the basis of these human elements that the hills were declared a World Heritage Site!

Given the importance of rain to the farmers several rain shrines emerged in the Matobo. Interrelated but separate, many of these shrines are still active. They lie at the heart of the spiritual importance of the Matobo. One, Njelele Hill in the south-western part of the hills is a regional shrine visited by devotees from as far as South Africa, Botswana and Zambia. Its significance to the believers is strong and it is not open to casual visitors, nor in the opinion of the author should it be.

The hills have always been a place of refuge during troubled times. People from other areas would hide in the hills drawing on the local and hidden food supplies and the ample water supplies that are a feature of the hills. The hunter-gatherers took refuge from the farmers; the Kalanga hide from the Ndebele; the Ndebele in turn took refuge from the invading colonial army of the Rhodesians; and then there were conflicts of the pre and post-Independence civil wars. There are many battles and skirmishes in and around the Matopos. It is a landscape of not only religion and joy, but also one stained with blood and sadness. It has been a key location in forging of the modern nation of Zimbabwe.

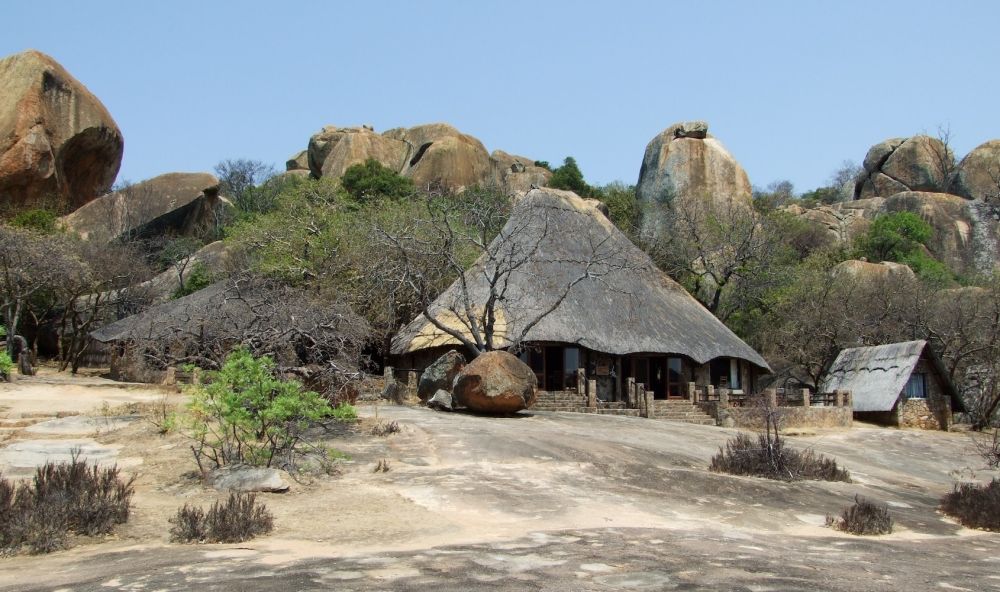

Big Cave Camp

Today the heart of the Matobo Hills is a national park. To most visitors it is a wilderness of rugged landscapes, wooded valleys and grassy vleis (wetlands). There are several public campsites and a variety of self-catering cottages within the Park. They are run in the main by the Parks Authority, although a couple of private initiatives are currently being finalised. On the margins of the park there are currently five commercial lodges catering for a variety of levels. Three are upmarket – spacious accommodation nestled in the rocks with swimming pools, guides and full-board – and include Camp Amalinda, Big Cave Camp and Scott & Sanderson Tented Camp. In addition several tour operators, including African Wanderer, run regular trips into the Matobo from Bulawayo, so you don’t have to stay out in the bush!

The Matobo Hills is an ancient landscape. Its hills have witnessed millennia, barely changing their profile. It is the living forms that have come and gone – the plants, the animals and we its people. The ancestors may have gone, but an undeniable human spirituality remains. It is this intangible uniqueness that sets aside this unique part of Zimbabwe. Those that come to appreciate the Matobo rarely escape, always yearning to come back.

Matobo Hills