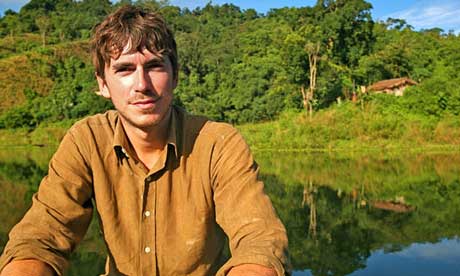

Simon Reeve made a tense visit to an off-limits corner of Burma. We asked him, is this really a country for travellers?

Struggling through the Burmese jungle at 4am:

Fleeing from an army patrol, I began to wonder if it had been an entirely wise idea to trek illegally into one of the world’s most repressive countries. I was travelling around the Tropic of Cancer, the northern border of the beautiful but blighted Tropics region, for a BBC TV series of the same name. With a BBC team I had travelled from Mexico across North Africa, over borders that had been closed to foreigners for decades, then on across the Arabian Peninsula to Asia. It had been spectacularly eventful and exciting, with moments of fear and terror, but inside Burma it occurred to me that the team and I might finally have pushed our luck a little too far.

Our Burma escapade had started in the little-known state of Mizoram:

In the forgotten north-east corner of India, where we evaded the authorities, travelled to a remote area of the river border, then took a local smuggler’s zip-line from the world’s largest democracy into Burma, a country with a feared military dictatorship.

Guided by Cheery Zahau, a fearless Burmese exile from the Chin ethnic group, we set out for a village in the Chin area of the country, trekking through sweltering jungle, crossing more rivers, then climbing into the hills. We had tried to prepare for anything, carrying ropes, machetes, trauma kit, camouflaged hammocks, locator beacons, food and survival kits. But we knew there were more than 50 Burmese army bases in the area; an encounter with a Burmese army patrol could end in disaster for us, and likely execution for Cheery, who was already on a Burmese government wanted list.

So we moved swiftly and quietly on our long, sweaty march.

With scouts ahead and behind in case of contact with soldiers – before we finally stumbled into the Chin village. The Chin in that area had never seen foreigners before, but they were desperate to tell the outside world about their treatment at the hands of the Burmese army. Cheery explained that forced labour, torture, rape, arbitrary arrest and summary execution by soldiers are commonplace here, part of a government policy to suppress the Chin people.

It was a tense visit.

Made more frightening when we learned, late at night, that a Burmese army patrol had arrived in the next village and was likely to be visiting our hosts. Fearing for the safety of our guide, the villagers and ourselves, we packed our kit and fled into the darkness.

All this happened a long way from the touristed areas of Burma, but continuing attacks on the Chin and other ethnic groups raise new questions for me about the ethics of visiting Burma as a tourist, just as [democracy activist and Nobel Laureate] Aung San Suu Kyi is thought to be softening her stance on the issue.

So, should you go, or avoid visiting Burma?

It’s a tough question, and one I can’t entirely answer.

I’m a great believer in the importance of travel and tourism. It can inform and educate the traveller, and benefit people in the country being visited. But in states where the son of the president has the national monopoly on luxury hotels, or the ruling military regime vacuums half the national tourist revenue into a Swiss bank account for the purchase of nasty new weapons, how can we justify contributing our hard-earned cash? We might as well send the secret police a box of cattle prods and save ourselves a flight.

The key to travelling anywhere:

Of course, is to visit with your eyes and mind open, and to use the services of local companies that put their earnings back into their community, not the pocket of a government official.

No Wanderlust reader would blind themselves to the local reality in any country they visit. But if you’re thinking of visiting Burma, my personal view is that simply opening your mind isn’t quite enough. Just as you might carbon offset, perhaps you should politically offset your travels, telling friends and family back home what you see, posting your experiences on the internet, and supporting democracy activists and anti-poverty campaigners. But don’t take risks while you’re there, otherwise – like my team and me – you might have trouble getting out.

In our case it was local Chin villagers who saved us:

Leading us through the jungle in the middle of the night and back to the Indian border, successfully avoiding military patrols along the way. We crossed the raging river back to safety, and all felt as if a noose had been lifted from around our necks. During my short time in Burma the stories I was told by the Chin ensured I could never forget I was inside a country ruled by a repressive, authoritarian regime. If you choose to visit Burma, that’s something I would also urge you to remember.