In the Shadow of ProgressAs I peered out through the curtains of my room on the fourth floor of the teachers’ accommodation block, it was as though I had crash-landed on a lunar landscape or been sent forth into the future to some post-apocalyptic industrial wasteland. Ice and snow covered the ground in places. On the horizon, the empty shells of massive apartment blocks and mighty warehouses stood jutting out of the earth. Strangely, the roads nearby looked new, with freshly paved foot-paths and recently erected light poles amidst the patchy dirt-covered snow. There was not a single soul in sight. The scene was only left wanting for a lone pair of sneakers hanging from a telephone line or a single tumble weed rolling by in the wind. I had landed in the Kaifaqu Economic Development Zone.

In the Shadow of ProgressAs I peered out through the curtains of my room on the fourth floor of the teachers’ accommodation block, it was as though I had crash-landed on a lunar landscape or been sent forth into the future to some post-apocalyptic industrial wasteland. Ice and snow covered the ground in places. On the horizon, the empty shells of massive apartment blocks and mighty warehouses stood jutting out of the earth. Strangely, the roads nearby looked new, with freshly paved foot-paths and recently erected light poles amidst the patchy dirt-covered snow. There was not a single soul in sight. The scene was only left wanting for a lone pair of sneakers hanging from a telephone line or a single tumble weed rolling by in the wind. I had landed in the Kaifaqu Economic Development Zone.

Kaifaqu is about an hour outside the city of Yantai in Shandong Province on China’s east coast. I had come to Yantai to participate in a volunteer placement as an English teacher at a local high school. In China, school begins at the age of 8 and continues until the age of 20. There are four grades of elementary, junior high and high school respectively. Yantai Kaifaqu Development Zone Advanced Middle School (YKDZMS) is indicative of many middle schools in China, where students from around the Province board at a centrally located school.

YKDZMS, where I lived and worked during my placement, has 3000 students and 200 teachers. The school entrance is guarded by school police, no older than the students they police, adorned in mismatched hand-me-down military styled uniforms. They stand firm with wide smiles, in the gatehouse next to the mechanical gate that is operated from their control post. The national flag is immediately visible upon entry to the school grounds. The teachers’ rooms and administration offices are housed in the first building to the right of the compound. The brickwork is red, with blue-green reflective glass that covers the front of the building completely. The same glass covers the upper areas of subsequent buildings, giving the impression of a modern and efficient school. The area between the buildings on the left and right of the inclined concourse is arranged in slowly rising steps, with short hedges filling the centre of the concourse in front and behind the flag poles. There is a large red structure, in the middle of the compound. Two huge arrows point toward the sky, surrounded by an orbiting swirl of red, with a golden ball balancing on it. It resonates of the future, technology, national advancement.

A musical alarm sounds at 06:00. Breakfast is served at 06:20. First classes begin at 07:00. Classes are 40-45 minutes long with 10 minute breaks between. At 10:20 students assemble in the quad to perform callisthenics. Lunch is served at 11:40. An afternoon nap is required for students living on school grounds. Dormitory doors are locked with bike chains. Students who live nearby may leave the school and return before the next class. Classes recommence at 13:30. Dinner is served at 17:10. 4 classes are taught before lunch and 4 classes are taught after lunch. Another 4 classes consisting of revision and homework continue after dinner.

Musical interludes and sirens blast the school grounds at different times of the day. The standard Big Ben bell is clearly much too understated for the likes of the advanced middle school, so Celine Dion plays in full voice at dinner time, some ramped-up version of Beethoven complete with funky bass-line, rocks after naptime and classical melodies fill the corridors between classes.

As 11:30 ticks over on the clock in the computer program that runs the school bells, a track by Enya plays to mark the beginning of lunch. The soothing tones of Enya flow out through speakers some of which are disguised as natural objects at various locations around the school grounds, washing over the shin-high topiaried hedges and shrubbery in the form of indistinguishable shapes, lifted on yonder high by the cool brown grit-filled breeze. In juxtaposition to these images of calm oddity, 3,000 near-sighted teenagers charge to the mess hall, like a herd of wild beasts in flight from a desperate predator.

Chaos rules as students queue at different stations along two walls of the dining hall and vie for position to be served food from the kitchens before it goes cold. Everybody fails. Food is paid for using a swipe card at a register that is mounted at a teller-like window. Students choose the dish they would like and serving staff fill appropriate compartments of an aluminium tray with the chosen food. A variety of food is available, from the left-over donkey dumplings from breakfast, to steamed rice to sweet and sour not-sure-what. The dining hall is arranged like a prison mess hall with long metal tables which the students sit at to eat with all the grace and manners of feeding time at the zoo.

In the Shadow of ProgressMess hall is not a term used lightly. With 3,000 students who have spent the greater part of their lives within one of the nation’s houses of learning, they can’t avoid showing signs of institutionalisation. With no parents and no teachers present, the latter knowing better than to eat at the school canteen, these children grow up with a distinct lack of table etiquette.

In the Shadow of ProgressMess hall is not a term used lightly. With 3,000 students who have spent the greater part of their lives within one of the nation’s houses of learning, they can’t avoid showing signs of institutionalisation. With no parents and no teachers present, the latter knowing better than to eat at the school canteen, these children grow up with a distinct lack of table etiquette.

When I asked my students about their plans for the future, many responded with nationalist rhetoric. They spoke of love of country, duty, serving the nation. One student’s favourite Chinese Festival was Army Day, because she loved her country, and she hoped one day to serve her country as a soldier. Other students felt tangible pressure to fulfill their obligation to the state. One student said she had no choice but to study chemistry and maths as the school recognised her talent in these areas and that she was obliged to fulfill her duty to the nation. These students are the elite, who entertain notions of university. Hundreds of their classmates may never have the opportunities afforded by further education. The infrastructure around them rises from the ground, as the state casts an ominous shadow over their future.

One morning a week I would cross the school quadrangle, through the junior’s building and on toward the school gates. A mini bus would drive up to the gates at exactly 8 a.m. to pick us up and take us to Kaifaqu Number 5 Middle School, the village school. We would make our way along the length and breadth of Kaifaqu, seeing nothing but piles of red dirt unearthed by big yellow machines on large black wheels. Small grey concrete ghettos dotted the landscape short distances from the road. People with their heads down against the sand winds and wrapped against the cold, making their way to the local bus stop on their way into the city to work. They seemed to appear magically out of the morning mist and snake their way out from between the low orange mounds. Their farms had been re-appropriated by the state. They had been removed from their land, forced to look for work wherever they could find it. Kilometre after kilometre, the landscape remained the same. Bulldozers displacing, then pushing piles of dirt. Men at work with tools of wood and iron, as if trying to move mountains one shovel at a time. You can feel the angst in the air, falling heavy against the cold hard concrete and steel, the middle ground filled with the sight of cranes on empty shells of buildings built for an industry yet to come.

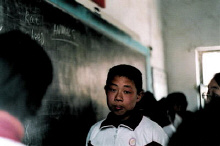

A compound of several rows of concrete buildings made up the classrooms and school offices. Each week, the headmaster would welcome us with offerings of fruit and tea and cans of cola. We waited in the office, drinking tea until a student arrived to escort each of us to a class. Rickety old wooden doors painted green banged together in the passing wind. I was met with a class full of faces beaming with smiles. The classroom was rudimentary. The blackboard was no more than black paint on the rendered concrete wall. A small platform in front of the board and a barely standing table for the teacher. The students sat at small wooden desks, their books piled in front of them. The walls were essentially bare. Most students wore some description of the school sports uniform, usually just the tracksuit zip tops, the colours white, with strips of red and navy blue and a pair of jeans and sneakers, some with a winter coat for warmth. All four classes I taught were enthusiastic, their English level fair, for ages ranging around 13-15. They seemed happy go lucky, their outlook bright and positive, if a little reserved. They seemed genuinely happy to see me and I was instantly glad to have made the trip across the Kaifaqu wastelands.

Some students live at the school. They stay in small rooms, in bunk beds, with up to 15 students in a room. No space, no privacy, no unsanctioned play or rest. They study from 6 a.m. to 9 p.m., with lunch at 11:40 a.m. to 12:00 p.m., followed by an afternoon nap that is strictly enforced by patrolling guards of teachers and senior students who peer through bedroom windows, taking down the names of miscreants to be reported to their parents. They are only allowed home on the weekends or if seriously ill. Still, the teachers seemed sincere, the students grateful and respectful.

In the Shadow of ProgressThe image of their smiles stayed with me as I made the return trip to my home school. A sweet sadness rising as the Kaifaqu landscape swept by. Destiny has placed these students in a development zone, yet perhaps they are destined only to fill the empty spaces that haunt the surrounding Kaifaqu area. Located within a system that aims to produce armies of ready, willing and able bodies to enter the labour market, many of the hundreds of students I taught during my placement, may never have the opportunity to develop beyond the confines of Kaifaqu’s cold embrace.

In the Shadow of ProgressThe image of their smiles stayed with me as I made the return trip to my home school. A sweet sadness rising as the Kaifaqu landscape swept by. Destiny has placed these students in a development zone, yet perhaps they are destined only to fill the empty spaces that haunt the surrounding Kaifaqu area. Located within a system that aims to produce armies of ready, willing and able bodies to enter the labour market, many of the hundreds of students I taught during my placement, may never have the opportunity to develop beyond the confines of Kaifaqu’s cold embrace.

Separated from their families at an early age, China’s young people are institutionalised and forced to conform to the state’s mandate; trained to work, rest and play to the beat of a state-sanctioned musical soundtrack. Revisionist history books and censorship act like cultural Prozac, numbing its citizens into a state of mild national fervour. China advances, buoyed by the strength of its labour market, while in the pre-industrial wastelands of its Development Zones, the futures of its children are systematically bull-dozed and buried beneath mounds of orange dirt.