Located on the eastern periphery of the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong province, Huizhou can feel a world apart from the surrounding industrial?region of the Pearl River Delta – China's manufacturing powerhouse.

Urban upstart cities like nearby Dongguan and Shenzhen might outsize and outpace Huizhou (sounds like 'hway-joe'), but old Goose Town’s lakes, waterways, and verdant hills, not to mention its many historic attractions, make it the perfect antidote from the rush and clamour of modern China.

The delight most feel when first confronted with Huizhou’s West Lake is not unique. The Song Dynasty scholar Su Dongpo (also known as Su Shi) was equally awestruck.?Su hailed from Sichuan province, but had grown to prominence in the Song capital, Hangzhou, only to be exiled from the court for his contrarian views.?In those days, anywhere south of the Nanling Mountains – which long sequestered far south China culturally and geographically from the rest of the country – was deemed barbarous, a malarial swampland on the very edge of civilization. Yet Su was genuinely taken by his home-of-exile, waxing lyrical about the local scenery, wine, tea and exotic fruits. Over his three-year stint in Huizhou, beginning in 1094, Su penned more than 500 verses ode to Huizhou and its people.

Today, Su’s lyrical endorsement is celebrated in the Huizhou West Lake Scenic Area. His?poems have been carved into sculptures lining the Su Embankment, which leads towards Huizhou’s must-have photo, the Sizhou Tower – an 80-metre-high, seven-storey, hexagonal Buddhist pagoda first constructed during the Ming dynasty.

In and around the Su Dongpo Memorial Hall, there are several sculptures depicting?the wise and benevolent scribe enjoying southern life. The hall itself houses a collection of Su’s calligraphic verse. There’s limited English language information, but it’s a pleasant place to walk around, as its design is based on the classical Chinese gardens synonymous with the Song dynasty.

Opposite the Memorial Hall, one can follow the Jiuqu ('nine bends') Bridge across Diancui and Fenghua Islands. The islands afford shade from the subtropical sunshine and are a great place to watch people potter about on pedal boats.

On the lake’s north shore, there’s more history to uncover, both religious and revolutionary. Tucked away in an old, mottled neighbourhood is Yuanmiao Temple, which was first constructed in 748 during the Tang dynasty, though it was damaged during the Cultural Revolution. Rebuilt again in 1990, this is incense-imbued homage to Lao Tzu, the philosopher at the heart of the Taoist tradition, is very much a living temple and a place where Huizhou folk come to venerate the gods (and presumably pray for some good fortune).

Indeed, exploring the Revolutionary Martyrs Park located just behind the temple, one is struck by how outmoded the striving proletarians appeared when compared with the temple’s saintly effigies. Taosim might be far older than Maoism, but as China reasserts itself, ancient culture is enjoying a renaissance, while socialist realism is alas, very much yesterday’s look.

As if to reinforce?this opinion, a reconstruction of the Ming Dynasty city gate serves as another bold symbol that Huizhou is back in business. Walking through the gate, confronted by the surging Dong?River and the gilded new district of Jiangbei across the water, lie the remnants of the original Ming wall preserved along the riverfront. This is clearly the boundary between the old and new, the China of scribes and temples within, the China of malls and manufacturing beyond.

The final piece of Goose Town’s historic jigsaw – a statue of Sun Yat-sen – is located in a park just behind the old wall. The revolutionary credited with toppling China's last dynasty, the Qing, Sun is now revered as “the father of the nation” (though he was not a communist). Intensely proud southerners revere Sun mostly because he hailed from Guangdong province; Sun even led a popular uprising from Huizhou in 1900.

It can be thirsty work circumnavigating West Lake. Luckily, not far from the entrance to the Scenic Area is Miss X’s Café, a quaint, two-storey coffee shop decorated with local furnishings. Over a ?30 fruit juice, the friendly patron Miss Xia will offer advice about the surrounding laneways. The adjacent alleyway, Jindai Jie ('Golden Belt Road'), is among Huizhou’s most historic streets.

First constructed in 1389, the winding old lane was once the commercial hub of Huizhou. Family houses and ancestral shrines line the route, affording a rare glimpse of a way of life fast fading from view in modern China. Now earmarked for tourism, the street has a line?of antiques shops, selling everything from Mao Zedong posters to Ming porcelain.

In Su Dongpo’s poem,?Huizhou Yi Jue, Mount Luofu is lionised, making for an easy excursion from Goose Town. Two hours by bus through disconcertingly messy industrial hamlets does little to invoke much anticipation: clearly, times have changed since Su’s day.

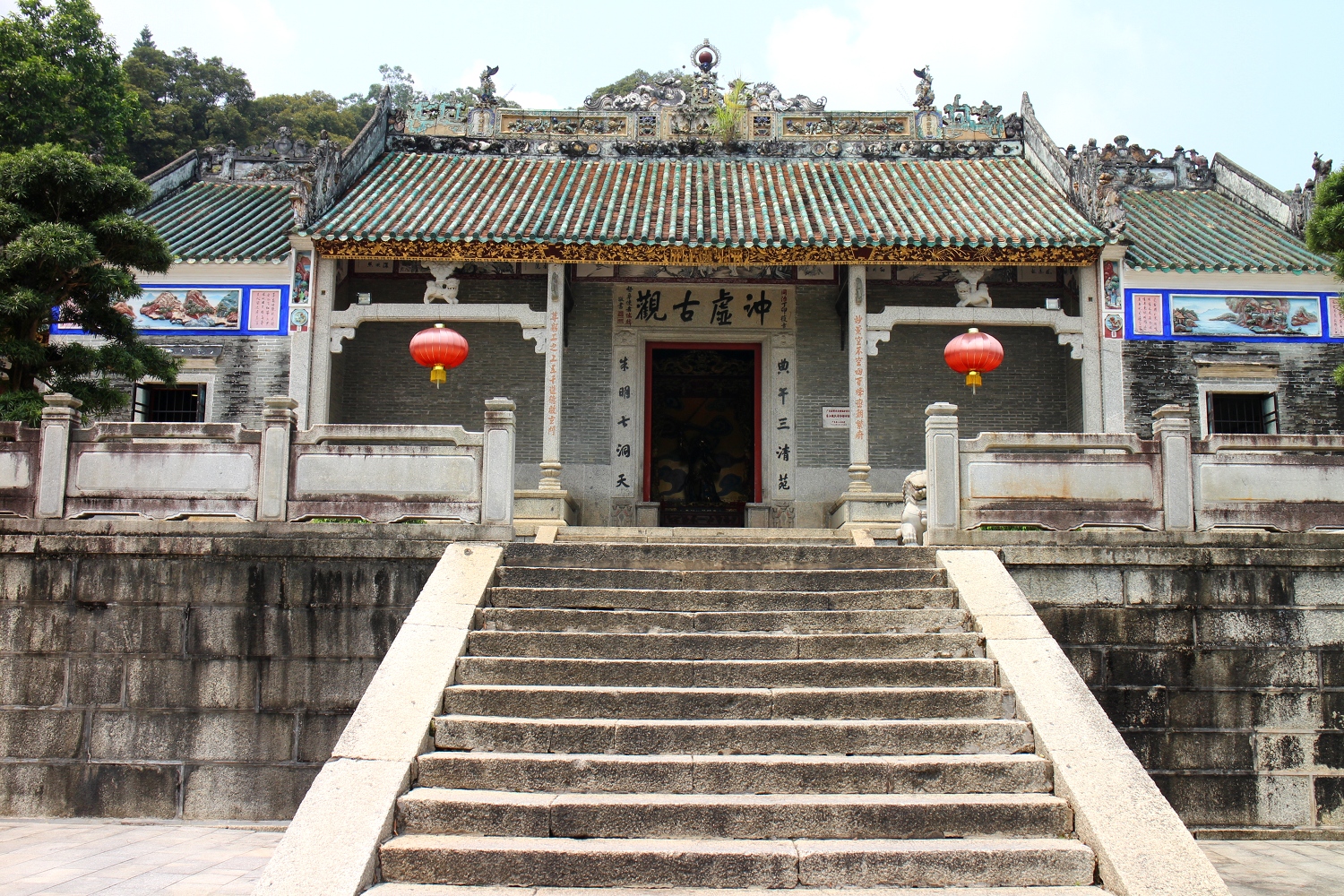

But the mountain, now a quintuple-A tourist site, is spellbindingly beautiful. The tapestry of history one finds around?West Lake is also weaved into the experience here. The central attraction is the beguiling atmospheric Chongxu Temple, first founded by Taoist abbot Ge Hong in 327, though it was rebuilt during the Qing dynasty.

It’s extraordinary to think a temple stood here in Su Dongpo’s day. Su is said to have first tasted lychee here, a spot now commemorated in the Lychee Virtue Garden.

In summer, the tropical climate can make climbing the mountain unappealing, but there is a chair lift to the top. The ride up offers a birds-eye of the abounding forest, making it hard to believe you are still in the heart of China's manufacturing region. During the final assent on?foot towards Luofu’s summit, you can’t help but feel a bit like poetry in motion.