Beyond their monumental size, earth buildings are unique for their jaw-droppingly robust architecture. Essentially castles or fortified villages, the multi-storey earth buildings were erected with a mixture of earth, sand, lime, glutinous rice, bamboo and wood chips, stoutly tamped into coffee-coloured walls up to two metres thick. They would expect a hammering in times of discord, so sturdiness was essential. Each stronghold could shelter hundreds of people ?– all sharing the same surname – and if danger approached, the iron-sheeted solid wooden doors would be swiftly bolted shut and weapons distributed among the men. Food would be stockpiled in advance and water drawn from wells within the building, so sieges could be drawn-out affairs.

The Hakka (in Mandarin: Kejia, meaning ‘guest people’) - who live in scattered pockets across south China and speak their own dialect - originally migrated from a central region of China around 1500 years ago. The name ‘guest people’ suggests a tribe on the move, which was once the case, as the Hakka were continually displaced by war, persecution or famine.

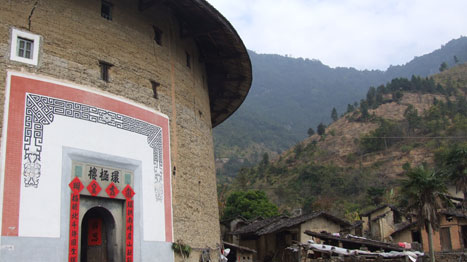

Sometimes called roundhouses, not all earth buildings are doughnut-shaped. Some are oval, square, rectangular or - more poetically - ‘five-phoenix’, and tens of thousands lie scattered across the region. Some earth buildings bunch up in picturesque clusters such as at Tianluokeng, Hekeng and Chuxi, but many stand alone.

Old-timer earth buildings may date to the 12th century but the youngest were only built in the 20th century. In a typical earth building - such as Zhencheng Lou not far from the town of Hukeng in Yongding country - families live in rooms leading off from wooden galleries arranged over three to five levels in a ring-like formation, which face onto a circular central courtyard. Kitchens are all downstairs with living quarters and windows upstairs. Within the courtyard - itself open to the sky and rain, sunshine and starlight - further concentric rings and corridors contained ancestral shrines and halls, tucked away beneath tiled roofs. The bulky walls keep the earth buildings warm in winter and cool in summer, or so locals attest. At harvest time, persimmons are everywhere, drying in the sun.

For anyone numbed by the impersonal nature of modern Chinese apartment blocks or the frenzied pace of urban China, the earth buildings are enchanting reminders of communal village life and the ancient rhythms of the agrarian southeast. In times of need, the Chinese frequently intone 'A nearby neighbour is better than a distant relative'. The earth-building-living Hakka have the best of both worlds, as neighbours are also relatives, as is the case in many traditional villages across China.

The Unesco World Heritage Site listing for numerous earth buildings highlights a growing sense of urgency regarding their preservation. Many earth buildings survive in a serious state of neglect or partial collapse. Not far from Zhencheng Lou, the Huanxing Building (Huanxing Lou) was torched by Taiping troops (the prevalence of wood made them particularly combustible) and was later badly damaged during fighting in the 1920s, leaving part of one wall missing. Other earth buildings are roofless shells, destroyed by conflict, while others bear the scars of earthquakes and conflagrations. Increased tourism is pouring money into the area, but rapid commercialisation is also eroding traditional livelihoods as earth buildings increasingly find a more rewarding future as museums.

Despite their sturdy defences, the earth buildings are also succumbing to a gradual hollowing out from within, as the Hakka once again move on. Like so many villages across China, grandparents and grandchildren can be found playing together, but there is often less sign of the labouring generation in between, who have left to earn money in the cities and towns, leaving many earth buildings depopulated.