Journalist and author Oliver Balch talks to Peter Moore about the rise of India and what it means to travellers

In India Rising, Oliver Balch takes the voices and stories of everyday Indians and presents a vivid account of the changes as they are unfolding. Travelling the length and breadth of the country, he leads readers off the tourist trail and onto the streets and dusty lanes of modern day India.

He speaks to Peter Moore about the changes he found in the India he first backpacked around 15 years ago. And the impact they're having on travellers.

Your book is presented as a series of vignettes, India as seen through a set of characters you come across in your travels. Why did you decide on that approach?

I’m fascinated by people. Their stories, their view of life, their experiences, what makes them tick. Travel gives you the opportunity to dip into other people’s worlds, and in turn learn about your own. That’s why I love it. So in that sense, a character-led approach came very naturally to me. But I think India lends itself to this kind of narrative. It’s such a diverse, contradictory, often confusing place. That makes it very difficult to make sweeping generalisations. So the book is unashamedly subjective. Yet my hope is that all the characters reveal different aspects of India, seen through their own eyes. Read together, their stories combine to offer a sense of the whole. A sense is not science, for sure. But isn’t offering a sense of a place what travel writing should do? There are lengthy textbooks for the other stuff. Or Wikipedia if you’re rushed.

Was this the book you set out to write? Or did India have its own ideas?

Reportage by its nature never turns out as you expect. You have to follow where the story takes you. My central objective was to find out how India is changing socially and culturally as a consequence of its recent economic growth. Beyond that, it was pretty much a blank page. My editor explicitly told me not to “go in with blinkers on”. That was great advice.

Personally, I think that’s the only way to write about a place as dynamic and diverse as India. Trying to shoehorn a previously determined framework into a book would be disingenuous. More than that, it’d just be impractical. India offers ten new questions for every one answer it provides.

What did you hope to achieve through this book?

I first went to India 15 years ago as a school leaver. I landed a job as a volunteer teacher in a Tibetan monastery near Darjeeling. I left after nearly a year absolutely enchanted with the country. For me, India was everything that the West wasn’t: spiritual, amaterial, ethereal. Then I started hearing talk of ‘New India’, this land of dot.com entrepreneurs and IT whizzes. I was interested in trying to reconcile these two opposing versions of the same place. I discovered neither were in fact true. Nor were they entirely untrue either. I think the book is richer and more interesting for discovering that such ambiguities are possible.

Which of the characters had the biggest impact on you?

It’s difficult to pick out a single character. Everyone I met caught my imagination or provoked my interest in one way or another. I guess Babu probably had the biggest singular impact on me. He’s also the guy I got to know best, which is perhaps the reason why. He’s a chauffeur in Mumbai, living in the same Colaba slum where he was born, struggling to get by, and yet quietly working hard to try and change his lot. His life and circumstances are so radically different from anything I’ve ever experienced. And yet for his reality is entirely normal. That sort of disjuncture I find very impactful.

Is Sunny, the journalism student you met, a metaphor for how you found India – all the trappings of modernity yet still conforming to anachronisms like dowry and caste?

In a way, I guess Sunny is a metaphor. New India is young and eager to get on. Yet Old India is still lurking, for good or ill. The two are sizing one another up. It’s a game of give and take.

Young people like Sunny find themselves in the midst of the convolution. His parents want to marry him off, while he’s wants to be with the girl he’s chosen. The decisions that his generation are making in these kinds of situations are precisely how the parameters are being negotiated for tomorrow’s India.

Tell us about Jeevan, the tribal villager in a remote corner of India, who doesn’t even know who runs the country. You seem to have found that part of India quite depressing. Why?

The ‘Shining India’ is obviously a fallacy, a piece of political marketing. That’s nowhere more true than in rural India. None of the benefits of India’s economic growth have trickled down to the rural villages where Jeevan lives. He’s a ‘tribal’, as India terms its indigenous. Without the skills to compete in the modern economy, this traditionally marginalised group is becoming even more cut off as India globalises. Urban India is changing so fast that they’re being left behind. What depressed me is the increasing difficulty that they face in ever catching up.

Yet it wasn’t all bad news. You did come across a village that had seized the initiative and were challenging the government on the right to manage its forest reserves.

That’s right. Both this book and my previous book about Latin America address some of the down-to-earth struggles and daily injustices under which many millions still labour. But there are people – amazing, visionary, courageous people – who are fighting back. I find their spirit hugely uplifting and inspiring. I like writing about these people as a consequence. Their stories are like chinks of light that brighten what can often seem like very dark and hopeless situations.

You talked to people from all aspects of Indian life. Was there any defining characteristic across all castes and financial position that you would say was distinctly Indian?

It’s difficult to say. I tried to steer away from generalisations. I think the one experience common to all Indians is the rapid speed of cultural change. In some places, it’s coming in floods. In others, only the first trickles are being felt. But it’s unavoidable. People’s responses are different, but the experience that tomorrow will not be like yesterday is pretty much uniform.

What do you see as the keys to India’s future?

Its youth. Much is said about India’s ‘demographic dividend’. Roughly half the country’s 1.2 billion citizens are under 25. Give them the right education, the right skills and the right opportunities, and the future could be theirs. Of course, better governance is crucial too. Corruption, mismanagement and social hierarchies all too often get in the way of young people achieving their full potential in India. But giving them the initial aspiration in the first place – that, I think, is key. Without that, the game is up.

Both India and China are cast as the next superpowers, economic powerhouses. What do you think are the differences between the two?

You’re right. We hear a lot about ‘Chindia’ these days. They both have vast populations, but they are markedly different places in reality. The Chinese economy is healthier in many respects because it lacks the chaos of India, for sure. That’s thanks to being a centralised government. India doesn’t work that way. Five year plans don’t last five minutes in India. Yet there’s nothing like a dose of chaos to inspire innovation. Indians are amazing at finding their way around seemingly insurmountable problems. It’s certainly a messier and less predictable way of going about things, but arguably it’s a whole lot more exciting. And liberating too, in every sense of the word.

You first visited India 15 years ago as a backpacker. What were the biggest changes you noticed between the India you discovered then and the India you came across now?

One answer: low-cost airlines. Well, low-cost airlines and litter. Both have grown exponentially.

So getting around was a different experience 15 years ago?

Flying just wasn’t an option in the mid-1990s. It was all buses on bumpy roads, and hot and sweaty trains. The trains are magnificent in India, though. I don’t think there’s a better way to see the country than through a grilled carriage window, together with the sing-song sound of ‘chai chai chai’ and the reverberations of the track ringing in your ears. I took the train whenever was practical, but I confess that I fell back on short-haul flights when time was tight.

You were also travelling with your wife and two small children. Was that a challenge? Any advice for people travelling to India with children?

It was both a challenge and an inspiration. We have two kids; one was five months, the other not yet two years old when we left for India. Of course it was difficult. We didn’t have a fridge, or a kitchen. We were based in Kerala, where it was insufferably humid for much of the year. Yet kids are amazingly adaptable. And immersing children so young in the sights, sounds and colours of India – that experience will inevitably shape them for the better in my opinion. My advice? Anti-mosquito cream.

Which parts of India would you suggest travellers seek out? Where should they avoid?

India is so diverse, it’s difficult to say. I’m torn between pointing people to the amazing palaces of Rajasthan and temples of South India, and alternatively advising them to jump on a random train and see where it takes them. Both approaches have their merits. For me personally, I love the mountains. I went to Ladakh for the first time on this last trip. Just stunning.

How long did the trip take you? Where did you go?

I was in India for just under one year in total. I tried to do justice to the width and breadth of the country, travelling right up into the Himalayas and right down to the southern tip. The biggest changes are being seen in the large ‘metros’ as India calls its mega-cities, so I spent a lot of time in places like Mumbai, Delhi and Bangalore. But I made a concerted effort to include smaller towns that few outside of the country would know, like Vijaywada, Gadchiroli and Mangalore. I ensured that rural India got a look in too. I spent a memorable day with Unilever in Andhra Pradesh, for example, seeing how they’re flogging shampoo sachets and water purifiers to poor villagers.

What were your favourite places?

We were based in Fort Kochi, in Kerala, of which (despite the humidity) I became very fond. They have this crazy street called Palace Road, which feels like the whole of India in microcosm: temples, shops, rickshaws, cows, hustle and bustle, everyone living cheek by jowl. I have a soft spot for Darjeeling as well. That’s where I was based during my time as a teenage volunteer, in a small village with a stunning view of Kanchenjunga (when the clouds lifted, that is).

Finally, to sum up, what are the challenges facing India? And did you come away with hope or despair for India?

There are lots of reasons to be negative about India’s future. The corruption, the bad administration, the general chaos. But I’m broadly optimistic about where the country is heading. I left with an overwhelming impression that a switch has been turned in the heads of the young. For the first time in India’s modern history, they have reason to hope that their lives might be not just repeat those of their parents. For some, arguably for many, that promise will prove to be a pipedream. But for the millions of India’s poor, the simple act of dreaming is a luxury that Old India never allowed them.

One more question: what’s your next project?

Having done two books now on huge landmasses – India and Latin America – I’m wondering if it might not be time to go to the other end of the spectrum and do something very local. I recently moved to the Welsh borders. Finding an excuse to go tramping in the hills with my notebook and pen – now that sounds like a project I could take on.

For more travel secrets from the world's most famous wanderers, visit our Interviews page.

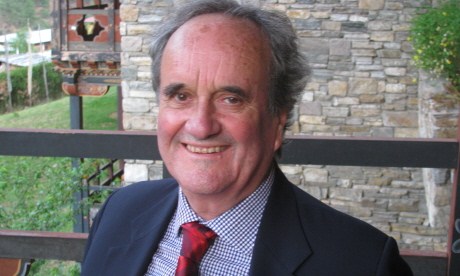

Sir Mark Tully: India. The Road Ahead

Sir Mark Tully: India. The Road Ahead

The BBC's former man in India talks about the country's future. And the places you must visit More

The Secrets of Wild India

The Secrets of Wild India

Leading wildlife filmmaker Harry Marshall talks about his new series that reveals India's little known wildlife treasures More

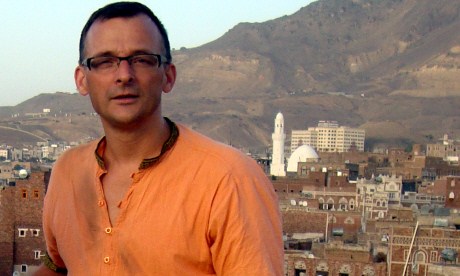

Travel in post-Gaddafi Libya

Travel in post-Gaddafi Libya

Arabist and author Johnny West on what the rebel victory in Libya means for travellers More