Beyond the bustle of India’s Golden Triangle lie quiet villages and desert camps that receive few visitors. Wanderlust-award-winning tour guide Sameer Singh Rathore leads the way

They’re not short of confidence, Rajasthan’s cows, but I couldn’t help feeling they lacked leadership.

Long-horned and short, bony and fat, they mooched through the pungent streets of Jaisalmer like teenagers on a school trip. They snacked on plastic bags, snoozed in the path of spluttering rickshaws, and made the odd lunge at a passing tourist. What they needed, surely, was someone to lift their heads from this rut and guide them to pastures new. What they needed was Sameer Singh Rathore.

Their loss was my gain. I’d come to India’s desert state to travel with one of the winners of last year’s Paul Morrison Guide Awards – in fact, the only guide in the world to be shortlisted every year the Awards have run. I’d met Sameer once before, in the oak-panelled auditorium of London’s Royal Geographical Society, when, after receiving his award, he took the microphone and delivered an impassioned speech on the plight of Rajasthan’s child widows. In the bar afterwards, the talk was all of this tall, compassionate, multi-lingual, cravat-wearing (and unmarried!) Indian, seemingly conjured from the pages of Mills & Boon. Women swooned. Husbands bristled.

Their loss was my gain. I’d come to India’s desert state to travel with one of the winners of last year’s Paul Morrison Guide Awards – in fact, the only guide in the world to be shortlisted every year the Awards have run. I’d met Sameer once before, in the oak-panelled auditorium of London’s Royal Geographical Society, when, after receiving his award, he took the microphone and delivered an impassioned speech on the plight of Rajasthan’s child widows. In the bar afterwards, the talk was all of this tall, compassionate, multi-lingual, cravat-wearing (and unmarried!) Indian, seemingly conjured from the pages of Mills & Boon. Women swooned. Husbands bristled.

Six months later we were rattling out of Delhi on the sleeper train into his home state. Born into the outer reaches of one of Rajasthan’s ruling families (“From warrior class to worrier class,” was one of his many bon mots), Sameer now leads trips combining the region’s numerous Unmissables with its Easily Missed rural alternatives.

In the few hours I’d been with him, he had already established impeccable guiding credentials: he was carrying a tube of glue to stick down any wayward Indian postcard stamps, a packet of Ayurvedic ‘magic green pills’ for the inevitable tummy troubles and a carrier-bag ‘snack bar’ for the peckish. Our small group had received a lightning briefing on the Hindu pantheon, a hand-painted map of our westward journey and a masterclass in railway-porter-payment etiquette. Now we just had to get some sleep.

“A couple of scheduled stops and a lot of unscheduled ones,” Sameer forecast cheerily, as we struggled to get comfortable on the barely padded, strap-hung beds. Around us the locals curled effortlessly into balls and proceeded to snore. The lights of the Delhi suburbs burned through fraying curtains. Sameer produced a bottle of whisky.

The next morning a milky sun illuminated a beige plain studded with twiglet-like khejri trees. We were in the desert. Some parts of this Marwar region – the ‘land of death’ – have not seen rain for generations. Rajput maharajahs used to make rain-effect toys for their children, Sameer told us, so that they wouldn’t be frightened if they ever encountered the real thing.

We disembarked at Jodhpur and headed further into the desert by road. If at first it seemed featureless, soon life emerged. A camel munched on scrub in the shimmering middle-distance, and a blackbuck gazelle with long twisted horns broke cover and scampered through rampant acacias.

After a while we turned off the road and entered Chandelao, a village of simple stone houses with blue-painted doors and broad, sandy streets patrolled by stiletto-horned, humped cattle. Women passed in those saris – fuchsia, indigo, vermilion, cerise, supernaturally bright against the dun earth, a colour palette the English eye can barely comprehend – carrying water on their heads.

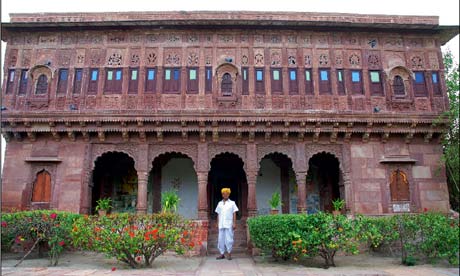

It was utterly picturesque but, sleep-deprived courtesy of Indian Railways, thoughts turned to which of these little homes might be ours for the night when we turned a corner and found ourselves, incredibly, at a fort. A castellated gatehouse gave way to a grassy courtyard scented with bougainvillea and hibiscus. Peacocks roamed the walls and the trees were a-screech with parakeets. We had arrived at the first of Sameer’s little secrets, where ‘Padi’ Singh, owner of Chandelao Garh, made us welcome.

All over Rajasthan, aristocratic piles are being converted into heritage hotels, but at Chandelao the conversion is saving the remote community the fort originally spawned. Awarded to Padi’s family in the 18th century for bravery in battle, the garh (fort) once housed a small garrison, but Independence and land reforms saw it fall into disrepair, leaving its dependent villagers adrift. Now travellers staying at the restored fort are helping to fund much-needed developments.

[page}

Sameer took us on a village tour – obligatory gaggle of children in tow – pointing out the newly installed water pipes, the improved sanitation system and a dim solar-powered computer room. Money has also been spent on buying in high quality breeding bulls, and – by the way they quietly menaced our party, forcing us to make looping detours through monstrous piles of dung – they know their value.

Chandelao’s flagship project is a craft shop, Sunder Rang (‘Beautiful colours’), where village women make intricately patterned cushion covers, clothes and toys in return for a fair wage. It’s the only way any of them can afford to educate their children, and anyway – their manageress smiled – it’s the best place to catch up on the village gossip.

But Chandelao isn’t just a worthy cause: it’s also a great base for exploring an austerely beautiful area rarely visited by foreigners. That afternoon we jumped into Sameer’s custom-designed, open-sided safari truck (formerly an inter-city minibus) and jounced along dirt roads past wildly waving villagers and ruminant camels. An Asiatic gazelle exploded out of the scrub next to us, its hindquarters bucking as it overtook us with ease. (“Just showing off”, said Sameer.) We passed tanneries and shrines, and visited one of the many nature-worshipping Bishnoi hamlets in the area, where a turbaned elder served us his opium-based homebrew (to no noticeable effect).

Wherever we went, one typical Indian experience was noticeably lacking: the begging. “Every time a traveller gives a kid in a village some money, it encourages the habit,” said Sameer. “So instead I give a little money to the village headman – the thakur – to use for everyone’s benefit.” It was an enlightened formula used repeatedly over the coming days.

Back at the garh, the sun fell but the colours in the villagers’ clothes and the quarried stone seemed to linger, as if innately glowing. No lights came on; there was nothing to mark the end of day. We dined on the battlements, looking out over the dark desert to the distant glow of Jodhpur. “This is what all villages were like before electricity, before tannoys,” said Sameer wistfully. “So peaceful.”

Jodhpur’s cows – encountered the next day – were less menacing than Chandelao’s, but even more smug. The ‘Blue City’ it might be, and historic seat of power for the Rathore clan (“very distant relatives”, insisted Sameer) – but the litter-munchers were in no doubt who was really in charge. Traffic held no fear for them: they slept in trios on the main highway, forming bovine roundabouts.

We ignored them and explored the city, which was like Chandelao magnified by 10,000. Here, too, was a raison d’être fort surrounded by dependent villagers, but in this case it was Meherangarh, a sheer-sided citadel shimmering with menace which has held off all-comers (Mughals, mainly) for five centuries. Beneath its cannonball-pocked walls lie the indigo-stained warren of Jodhpur’s townhouses. In one of those perennial Indian mysteries, nobody seemed quite sure why they’re blue – something to do with cooling, or insects? – but it’s certainly done wonders for tourism. Jodhpur is firmly on the Rajasthan circuit, and we duly did the necessaries. We marvelled at the cool geometries of the hilltop White Marble Memorial (built from the same stone as the Taj Mahal), and then braved the gladiatorial hubbub of Sardar Market, which sells more items than Harrods but seemed particularly well-stocked in flip-flops.

The next morning, at Meherangarh Fort, Sameer demonstrated one of the guides’ greatest skills: knowing when to make yourself scarce. Audio tours aren’t for everyone, but Meherangarh’s is introduced by a maharajah, gives you a thorough briefing on half a millennium of sex, war and desert intrigue, and allows you to wander, headphones on, through this astonishing building at your own pace. I drifted from battlements to boudoirs, as fascinated by the peacock parade of Indian visitors as by the endless architectural innovations designed to keep residents cool in temperatures that push 50ºC in summer. Air con may be cheaper, but it does lack the romance of a filigree screen dipped in perfumed water and hung at the door to catch any passing zephyr.

I would have settled for any kind of coolant as we stepped from our bus into the desert heat a few hours later. We’d driven north-west from Jodhpur to a flyblown cluster of camels slumped by the road to Osian: we were off the circuit once again, and back in Sameer’s hands. For the next two hours we loped through a weird landscape of low dunes and giant milkweed, the only sounds the rush of wind-whipped sand and the cluck-cluck of the camel drivers.

A camel safari is another of those umissable Rajasthan experiences, but most sorties depart from Jaisalmer or Bikaner to commercial desert camps – some even have swimming pools. Our destination was Dera Eco Camp, a low-key dozen tents in the lee of a dune on the opposite side of the Thar Desert. We’d travelled only a few miles from the road – for which our backsides were grateful – but lolloping up at sunset, with only a few goats and the odd deer for company, it felt like the desert belonged to us.

“There’s not another camp for 60km,” owner ‘Honey’ Bhati told us, as we dined on Sameer’s chicken korma by lamplight. “People said nobody would want to come here, but this kind of camp helps the local people to continue living traditional lives. Camels cost money: without visitors the local camel herders couldn’t afford them.”

Other locals took a little income from our stay too. After dinner, a group of musicians from a nearby village performed for us. Their tribe were traditionally snake charmers, but this family troupe had travelled far and wide playing their gypsy rhythms on jew’s harp, bagpipe and a giant tambourine whose skin had to be reheated over the kerosene lamp to keep it taut.

Under the stars, two mischievous girls with flashing eyes and twirling skirts cajoled us into dancing with them, before delivering their party piece: one of them took a ring from her finger, placed it on the sand and then – accompanied by frantic percussion – bent slowly backwards like a scorpion’s tail, until her head was level with her feet, and plucked up the ring with her eyelash. Sameer whooped his appreciation. “My God, I’ve seen her do that 20 times and I still have no clue how she does it.”

As the musicians packed up, Honey told me about the challenges of building the camp here – how sandstorms blasted away the tents, and all food had to be brought in from Jodhpur, and his manager had been stung by a scorpion, saved only by a healer who had chanted away the poison through the victim’s mobile phone. But despite all the tribulations – he paused and looked out over the desert, just as we had from Chandelao a few days previously – “I like it here because you can’t see any lights.”

But Honey was wrong. Jaisalmer was vigorously alive, and I fell for it ten paces inside the old city walls. Compact, self-contained and crowned by the oldest still-inhabited fort in the world, it’s a town made for strolling. A guided tour would have killed its thousand waiting serendipities, and Sameer knew it: he dropped us at the gates and waved us into the waiting streets.

Arriving in the late afternoon, I wandered up through a tumble of sun-splashed alleyways, watching the comings and goings of clock-menders and spice vendors, washer-women and knife sharpeners. I stumbled upon impromptu urban cricket matches, and fell into conversation with hoteliers who showed me centuries-old opium ‘minibars’ (and didn’t even try to sell me a room).

I got lost, and a teenage boy beckoned me through to a majestic panorama of Jain and Hindu temples, and then escorted me over rooftops and through washing lines – via his living room – down to the 19th century merchant houses, the havelis. And these havelis, wedding-cake skyscrapers, are knockouts. Mesmerising in themselves – intricately carved, sensuously planned – their aura is magnified by the complete lack of hoopla surrounding them: past their front doors rickshaws roar and cows, in great numbers, splat.

But from Jaisalmer’s beauty stems its greatest threat, and a symbol for many of the development issues Rajasthan faces. With tourism booming, water use in the drought-afflicted fort has soared, leading to dramatic subsidence – gaping cracks and wonky walls are everywhere. At the same time, the tourist economy has displaced others: streets are jammed with (admittedly easy-going) vendors of cushion covers, wooden elephants, Om T-shirts, satchels, internet access and ‘non-touristic safaris’ to nearby villages. And even in these villages – we made a short tour of crumbling settlements and NGO-funded new towns – there are signs of children learning the universal language reserved for foreigners: one pen, one photo, one rupee. “There’s nowhere in this region that hasn’t been touched by tourism,” Sameer told me simply.

But if that sounds off-putting (and it would have done to me ten days earlier), don’t let it be. I’d zig-zagged between places in Rajasthan that see a few dozen visitors a year and tens of thousands, and I wouldn’t have missed either. A great guide helps you discover iconic places for yourself, unveils secrets you’d never find otherwise, and takes you beyond sightseeing into understanding. Sameer had done it all with brio. The cows really were missing a trick.

The author travelled with The Imaginative Traveller (08450 778803, www.imaginative-traveller.com) on the first week of its 22-day Rajasthan Safari itinerary, which visits Delhi, Rajasthan’s main cities, Agra and Varanasi, mainly by private air-con coach. Accommodation is in a mix of heritage and mid-level hotels, overnight trains and a tented camp. The trip costs £1,495. Wanderlust award-winning guide Sameer Singh Rathore leads a variety of tours in Rajasthan and northern India exclusively for The Imaginative Traveller.