India's tigers are in trouble - Lyn Hughes catches a glimpse of the cats and the conservation issues in Ranthambhore National Park

"Can’t you see it, Lyn? Come here!” I clambered across the seats in the open vehicle and followed the guide’s finger as he pointed at the long grass, burnished gold by the late afternoon sun.

I stared and squinted, willing myself to see something – anything. Suddenly I glimpsed a twitch; I realised I was looking at an ear, a big yellow ear, attached to a large round head. How had I not seen the female tiger before?

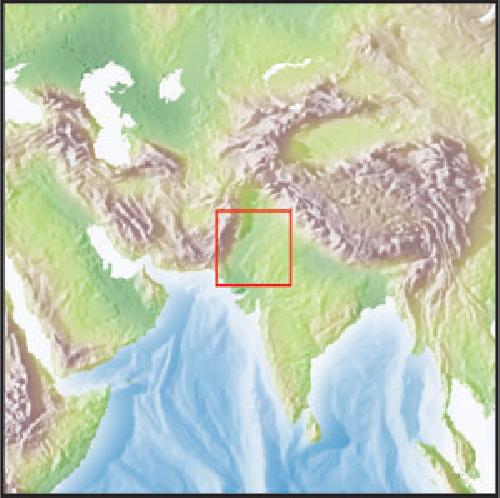

It was my first day in Ranthambhore National Park and I hadn’t been optimistic about my chances of seeing a tiger. The park, a staggeringly beautiful backdrop of lakes, ruined palaces and varied landscapes, was once a huge success story – the jewel in Project Tiger’s crown. From a critical low of just 15 in the 1970s, Ranthambhore’s tiger population trebled to 45 by 2000. What’s more, as the numbers grew, the tigers also became bolder, and were frequently seen in daylight hours padding the reserve’s sandy roads. What could go wrong?

The shocking news is that in mid-2004 local conservationists reported that at least 18 tigers were missing. Unofficial estimates now put the number of remaining tigers as low as 14 or 15.

The statistics are just as scary throughout India as a whole. An official census has been carried out, but the results have not yet been released. However, conservationists are speculating that numbers could be as low as 1,500, and accuse the government of being in denial.

Poaching is the biggest problem, its sharp increase due to the demand from increasingly affluent Tibetans for traditional-style, animal skin outfits known as chubas. The Dalai Lama has spoken out against this fashion, but with shops in Lhasa openly selling them, and television personalities publicly flaunting them, the future looks grim.

My visit to Ranthambhore waspart of the annual Festival of Wildlife, organised by Wildlife Worldwide. Held in a different country each year, the festival unites a bunch of enthusiasts with a team of experts on wildlife-related topics such as photography and art.

The festival kicked off with a film by wildlife artist David Shepherd, who has visited the park many times and painted some of his best-known works here. David, in turn, introduced us to legendary former director of Ranthambhore, Fateh Singh Rathore.

Fateh is now an honorary warden of the park, and inextricably linked with it. He gave an emotional and stirring talk on the current crisis: “I am optimistic. I still believe that we will save the tigers in this park, but I could be wrong. We are in a terribly critical situation. We need to get back to losing no tigers in a year. We’ve done it before and we can do it again, with the help of people like you.”

Unfortunately, Fateh Singh Rathore and his son, Dr Goverdhan Rathore, have made as many enemies as friends in their crusade. Driving to the park the next morning, we passed several bulldozed buildings – many of these had some connection with the Rathore family. Depending on who you believe, the authorities either destroyed them because they were illegal, or as an act of political spite for the Rathores’ role in highlighting the corruption behind much of the poaching.

I had joined one of the groups in an open vehicle known as a canter, which hold up to 20 people. You can only enter the park in an authorised canter or small 4WD (known as a gypsy); numbers are limited, and controlled by a cooperative. The park is relatively small, and a victim of its own popularity, so vehicles are allocated a fixed route, the number of which is displayed on the bumper.

The main entrance to the park is overlooked by the 1,000-year-old Ranthambhore Fort. The cliff-top complex houses several mosques and temples, including a significant shrine dedicated to the elephant-headed god Ganesh. Pilgrims visit from around India and, as we approached, we saw several making their way along the road, some fully prostrating themselves every ‘step’ of the way.

Entering the park gate we were welcomed almost immediately by cheeky langur monkeys hoping for a snack, and by the haunting cry of a peacock – one of those sounds immediately synonymous with the subcontinent. Within a few hundred metres we had seen our first chitals (spotted deer) and sambar (larger animals, reminiscent of red deer).

After 30 minutes the vehicle screeched to a halt as our guide, Ash, spotted the pug mark of a female tiger in the sand. “They’re fresh tracks and heading in the opposite direction. Let’s turn round and see if we can find her.”

A few minutes later another canter pulled up alongside and the excited occupants told us how they’d seen a mother and her two cubs half an hour earlier. “She’s gone into the undergrowth now. She’ll sleep all day and won’t come back until late afternoon.”

It was thrilling but frustrating news. I’m generally fairly lucky with my wildlife spotting, but two previous visits to India had failed to deliver any big stripy cats – and that was when numbers were on the increase. With the current severe crisis, I couldn’t help but feel a little pessimistic.

I did have to remind myself that there was so much more to see than the tigers. On that one drive alone we saw peacocks displaying, two chital stags fighting, a cute little collared scops owl hunkered down in the fork of a tree, and a painted stork, splashed with red, pink and black. Ranthambhore’s official bird count is 272, but some of the guides had seen many not on the official list and stated there could be at least 390 species.

We were fortunate to have our own guides with us, some of India’s best. The drivers were obsessed with looking for tigers – no wonder when they are put under so much pressure by the vast majority of their passengers. But we had to keep asking them to stop to enable us to watch the other wildlife, and not to move off again until we were ready.

On that afternoon’s drive we followed a different route. For a while there was little to see, until we came across a small group of nilgai, a large bluish-grey antelope, known locally as a blue bull. In the background we heard a warning call from a monkey, possibly alerting the forest to the presence of a leopard. There are believed to be 40 to 50 leopards in the park, although they are secretive and rarely seen.

Further on we heard the warning call of sambar, more likely to be announcing the presence of a tiger. Around the bend a scrum of canters and gypsys were parked by a clearing; 100m further on more vehicles had stopped, overlooking a dried-up watercourse. They had spotted a juvenile male, while his sister was just metres away from us, lying on her side in the long grass.

While thrilled to be able to make out the female, we longed for her to rise up and give us a clearer view. The sun was sinking in the sky and the temperature dropping so it could only be a matter of time before brother and sister, along with their mother, would be regrouping and heading off to hunt. Gradually the other vehicles left – bar the one with a park official in it.

“I’ve got to leave,” said our guide. “That’s the deputy director of the park and we’ve already broken the 15-minute rule sitting here. And we risk leaving the park after the official closing time which means our driver could get suspended and fined.”

Reluctantly we left, the dusk rapidly falling, and bounced out of the park as fast as the vehicle would go, just clearing the gate on closing time. At least I had seen my first tiger in the wild. The curse had been broken. I only wished that my late husband, and co-founder of Wanderlust, Paul Morrison, had been with me. He’d had some amazing travel and wildlife experiences but, if you’d asked him what was left on his very long wish list, seeing a tiger would have been up in the number one spot.

Over the next two days we continued to explore this extraordinarily beautiful park to a soundtrack of rutting stags, croaking frogs and the piercing call of the peacocks. We gazed in wonder at the second-largest banyan tree in India – believed to be around 2,000 years old – a herd of chital sheltering from the sun under its extensive canopy.

For one of our guides, spotting vultures riding the thermals was perhaps the biggest thrill. Once a common sight throughout the subcontinent, numbers have been completely decimated, with 98% of them falling foul of the veterinary drug diclofenac, which poisons them if they feed on a treated livestock carcass. “The drug’s being phased out,” our guide said, “but it’s hard to stop people using it.”

All too soon, it was the last drive of the trip. It was a hot dry afternoon, the air still. Rather than dash along the dusty tracks, we asked if we could spend some time watching Rajbagh Lake, second-largest of the lakes and arguably the most picturesque. Several sambar grazed in the shallows of the lotus-strewn water, a troop of langurs were chattering in some nearby trees, and there were at least 25 different species of birds within sight. As we peered through binoculars at a jackal trotting along the shore, a whispered rumour started: “Tiger!”

Across the lake, framed in a window of the ruined palace, was a magnificent 18-month-old male, gazing out imperiously. It was the brother of the female I had seen on the first day, the other half of the so-called ‘Lady of the Lakes’ cubs.

After ten minutes or so, the tiger disappeared into the shadows. We set off round the other side of the lake, hoping we might see him leaving the ruins. Finding a suitable spot, we turned the engine off and sat in quiet contemplation, just the gentle hum of insects and the occasional plop from the water breaking the reverie.

A shiver went down my spine as our guides tensed. We all grabbed our binoculars. The tiger appeared in an archway, and stood for a while as if trying to decide whether to head out or not. We groaned as it turned back inside. But a couple of minutes later it appeared again, looked around, then sauntered out, heading casually along the lakeshore.

The tiger lay down under the shade of a banyan tree, then moved a little further down the shore and rolled around on its back before disappearing into the long grass. We drove on, but couldn’t resist turning back one more time – just in case. Sure enough, the tiger was coolly strolling along the shore. After a few glorious moments it had gone.

That evening a charity auction was held in aid of the David Shepherd Wildlife Foundation. One of the lots, arranged with the park’s authorities, was the opportunity to name the male tiger that we had seen that very afternoon. I successfully bid for it, and named the tiger Morrison.

The author travelled with Wildlife Worldwide (www.wildlifeworldwide.com)

Ranthambhore National Park is open to visitors from October to June, closing for the monsoon from 1 July to 1 October. During the winter it is open from 7am until 10pm, in the summer from 6am until 9pm. The best time to see the wildlife is early in the morning or late in the afternoon, and drives are timed to reflect this. Temperatures may reach 50°C in May, but otherwise average around 30°C.

India Tourism (020 7437 3677, www.incredibleindia.org)

Project Tiger