Back to Pakistan: A Traveler’s Tale

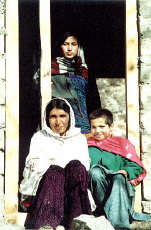

Women in Altit

![]()

![]()

At Peshawar’s normally full Tourists’ Inn Motel, we hung out with the two other guests: Will, a 30-year-old New Yorker who was putting together a video about the tense times in Pakistan, and Charles, a 30-something Englishman who was driving from England to India in his 40-year-old Land Rover.

Will and I would roam the dusty streets of this frontier town, where war raged just across the border, stopping at pro-Taliban fundraiser and blood-drive booths and buying up Osama bin Laden T-shirts to show our future grandkids. He would film away with his handheld video camera and I could click away with my Canon. Sure, most would say it was stupid of us, but not once did we experience the slightest problem.

While the covering of the head is not required in this Muslim country, I opted to respect the local female fashion code and always wore a large shawl wrapped around my head and upper body while in public. Of course that didn’t stop the locals from gawking at us, particularly at me, but it did, I suspect, result in a warmer welcome.

To my astonishment, some Afghan women shrouded in burkas, the head-to-toe covering with only a mesh opening at the eyes, would stop at the sight of this Western woman and silently nod their head hello. Some even hesitantly reached out to shake my hand.

Disappointed at the relatively relaxed scene in Peshawar, our little foursome rode off one Friday morning in Charles’ Land Rover for Islamabad, where there was to be what was being dubbed a wheel-jam, the striking of local transporters, as well as a general strike of shopkeepers. After midday prayers, pro-Taliban protestors were being called on to hit the city streets, and we were hoping to check it out.

As we made the three-hour journey to the capital, toll-booth employees, shocked to see tourists, eagerly waved us on and refused payment. Many even offered us a cup of hot tea; but, we had a demonstration to attend and there was no time for chitchat.

Much to our amazement, only a few hundred Pakistanis half-heartedly took to Islamabad’s silent streets, and it appeared to us that there were more journalists, eager for some sort of story, than there were protestors. Though in other corners of the country, tensions exploded that October afternoon, resulting in multiple deaths.

It was sad to break up this happy bunch of backpackers when Elaine and Charles headed off to India and Will and I moved up to the mountains of the north, but such is life on the road.

In the rough-and-tough mountain outpost of Gilgit, Rowena, an elderly British woman who calls this rugged territory home, warned us to be extra vigilant. Even before September 11, caution was key in some parts of the mountainous north, where in certain lawless regions tribesmen appear to rule rather than the government. In fact, three Western tourists were murdered in the mountains this past spring. Though the killings took place far from where Will and I were planning on venturing and well before September 11, it still made our hearts flutter faintly with fear.

Here in Gilgit some townsfolk were mourning the recent fall of Kabul, and so it would be best, she thought, for us not to be on the streets after dark. Will and I heeded her advice, though not once did we encounter any problems. Actually, many people, relieved to see the return of outsiders, were quite hospitable towards us, two of three visitors in a town that is normally bustling with tourists.

Just up the Karakoram Highway (KKH), which links Pakistan to China and which cuts through some of the most majestic mountains in the world, lays the Hunza Valley, long favored by tourists for its spectacular scenery and friendly mountain folk.

Hunza Valley

![]()

![]()

In the heart of the Hunza Valley, the normally tourist-packed village of Karimabad had only one other tourist in town when we arrived: a Japanese man who had been there for the past two months. When I inquired about his daily activities, he replied in broken English that he lays in bed a lot. Yet another oddball, I mused.

Lal Hussain, the affable old man who has been running the Old Hunza Inn for the past 22 years, lamented the lack of tourists. Generally in November there are 10-15 guests a night just in his hotel, one of 20 hotels in the now-quiet village.

Since September 11, Karimabad, heavily dependent on the tourism industry, has seemingly reverted to the days of yore before the KKH cut through this region in the 1970s, bring a wave of Gortex-covered tourists on its heel. This, however, suited Will and me just fine as we chatted with the locals and roamed the nearby hills, where we were even invited for lunch one afternoon by a couple and their seven children.

Our plan was to explore this strongly anti-Taliban region for five days, but, unfortunately, our trip was cut short as Will unexpectedly had to return to Islamabad.

Looking to find a computer from which to access e-mail, I returned with Will to Gilgit, the administrative and commercial hub of the north. Will has since moved on to Islamabad alone, and I have been in bureaucratic purgatory as I try to find out when the border with neighboring China to the north is slated to re-open.

Cautious Chinese officials sealed off this economically strategic border soon after September 11. With the days of the Taliban seemingly numbered, frustrated businessmen on both sides of the border are anxiously awaiting its re-opening so that the vital trade that runs up and down the length of the KKH can resume.

My plan in September, during my first foray into Pakistan, was to traverse the KKH on my way to the ancient Chinese city of Kashgar, once an integral link on the historic Silk Route, where I hoped to visit the famous colorful Sunday market.

Looking to put to use my Chinese visa, I am still hoping to make it into the People’s Republic via the Khunjerab Pass, which at 4,733 meters is the world’s highest tarmacked-road border crossing. But I am going through governmental hoops as I try to secure a re-entry Pakistani visa, thus ensuring that I don’t get stuck across the border in western China.

However, hanging out in Gilgit, where snow-capped mountains and a baby-blue sky surround this little town, isn’t a bad gig. Mornings are spent surfing the Internet, as I catch up on the rapid developments against the dying Taliban regime and take tea with the friendly Internet cafe clerk. Afternoons I aimlessly stroll the fascinating markets, snatching up much-needed winter clothing at rock-bottom prices; ride on the back of small Suzuki trucks, which serve as shared taxis, with the cool winter wind blowing through my hair; and snap photos of these colorful mountain characters. And evenings, when the dimly lit streets become eerily quiet, I return to the Medina Hotel, where I am the only guest, and huddle in front of the gas heater, reading and writing in my journal.

Granted, it would only take one radical jihadi to end not only my trip around the world, but also my life. But with each passing day it becomes more and more clear that Osama’s cause is quickly losing steam, and I became more and more comfortable being one of a handful of tourists in Pakistan, a country where I am being surprisingly warmly welcomed. If you want to experience a country as it was before the age of mass tourism, during a war, I am finding out, is a pretty good time to travel.

——–