It was a combination of the tears on their faces and the high, warbling wail that ran chills down my back. It’s a bit odd, from our cultural standpoint, to just turn up at the funeral of some guy you’ve never met. Nicholas assured us it was fine, expected even, and that the more people turned out, the more honored were the dead man and his family. Nonetheless, it felt awkward to pass beneath the balcony with black veiled woman weeping and be escorted to our seats by a son-in-law of the deceased.

We drank the obligatory tea, cloyingly sweet, and munched on a plate of finger food that our hostess provided: some delicious cake, two sorts of psuedo-rice krispie treats and the rice flour and palm sugar snacks rolled in sesame seeds that I can’t quite stop thinking of as sweet cat turds.

The boys quickly made friends with a tribe of local kids while Nicholas brought us up to speed on Torajan funerals and this particular family.

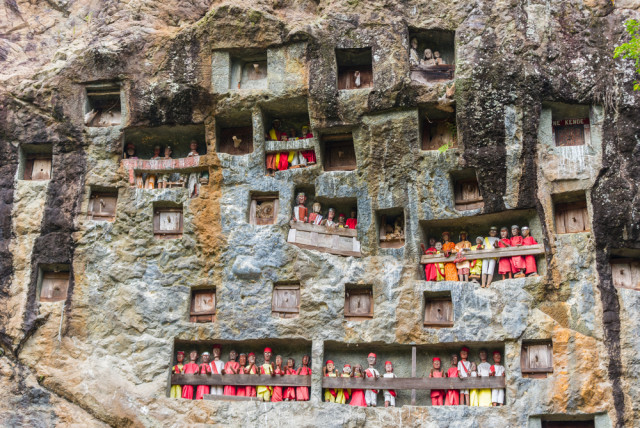

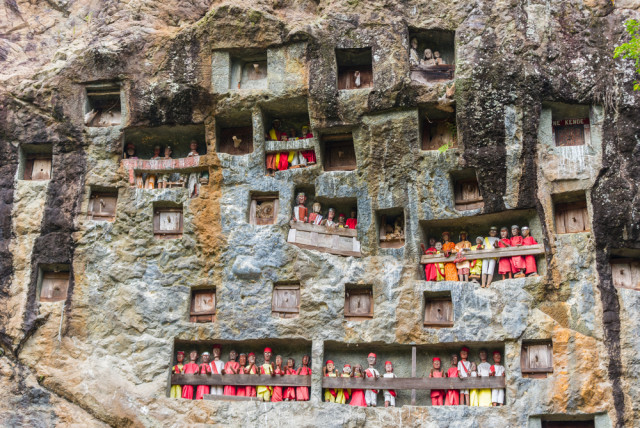

I quietly wonder who they were. I stare into the worn eyes of their tau-tau and wish they could answer the questions I have. Their statues stand their endless watch, and I wonder what they make of our pale faces, strange clothes, and language. In that moment, the world seems a miraculous time machine to me, with hidden portals where worlds touch, threads of history almost intersect, and the tau-tau almost come to life and tell their story.

The baby grave tree was scary to me before I saw it. All I could think of was the other horrible tree that we saw in Cambodia this past summer. The one under which I was brought to my knees in gasping, mama sadness for the horrors perpetrated there. This was an altogether different sort of tree.

According to the ancient beliefs of the Torajan people, a baby who died before his first birthday must be buried in a tree. In this way, the baby could grow up and out through the tree. The babies were carefully wrapped and placed inside hollowed out spaces in the trunk of a growing tree and covered over with palm fiber doors. The hope being that their essence would become part of the tree. I like that thought. I like it a lot.

It seems like the Torajans are obsessed with death. But really, it’s just the opposite. They are celebrants of life in some of the most beautiful ways.

The thought crossed my mind, as we bumped along the nearly impassible roads, listening to Nicholas tell us stories of his people and his history, that, on the surface, it seems like the Torajans are obsessed with death. But really, it’s just the opposite. They are celebrants of life in some of the most beautiful ways.

When their people die, they keep them in the house for a long time, allowing time to grieve, time to let go, time for life and death to fade together gently. Death isn’t the sharp cutting of a cord and immediate detachment that quick burial is. I kind of like that.

They craft tau-tau in the image of their loved ones, preserving a piece of them for future generations, as well as telling the stories through faces and eyes. They are amazing likenesses, some of them, and the very best of familial art.

They’v transformed death into something living, with their infant burials, a really lovely connection made between animal and vegetable, short lived, and long growing.

Death isn’t something to be separated from life. It’s merely the next step that we all take, and in this place the ghosts seem to hold hands with the living.

Have you ever attended a family event in another country where the cultural differences were as dramatic as the story above? Share your story below.