Matthew Teller proves to us that Petra can be done on a short break

No problem,” he said. “Just watch out for the water snakes.”

Standing at Wadi Muthlim, one of the gateway gorges to Petra, this is not what I’d expected to hear. Since when do you get water snakes in the desert? This would have made ophidiophobic Indiana Jones think twice before his Last Crusade, as it did me – was I ready for the snake challenge?

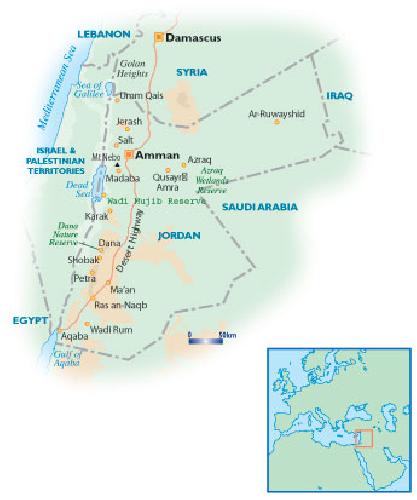

Until then, this had been a fantastic trip – Jordan was exceeding expectations. The Middle East’s most versatile all-rounder – boasting mountains, beaches, castles, ancient churches, semi-jungle and sandy deserts – Jordan is a compact country stuck in the worst of neighbourhoods. With Israel and Palestine on one side, Iraq on the other, Syria to the north and Saudi Arabia to the south, who needs enemies?

Sadly, this essentially peaceful, stable, cultured and exceptionally friendly place has suffered from everyone else’s bad press: you’re safer in Petra than Pisa, but don’t expect the newspapers to tell you that.

I was here to test out a theory: to see if a short break to Jordan was viable. With limited time, planning was going to be key. BA’s Thursday-night flight went via Beirut, getting into Amman at 3.45am: handy for avoiding a first-night hotel bill, but certain to make Friday gritty-eyed. So Royal Jordanian it was, with a late-afternoon departure arriving at 11.20pm. A fax took care of booking the airport hotel, another sorted out a rental car – I was all set. Everything ran smoothly, and the following morning we were careering south down the Desert Highway while Britain still slumbered.

The road was fast and functional, slicing through a fairly featureless landscape for a couple of hours before reaching the edge of the highland plateau at Ras an-Naqb, where the vastness of the Arabian desert stretches out in a magnificent panorama. The view never ceases to amaze me and, judging by the impressive crisscross of skid-marks on the tarmac, I’m not the only one.

Even with a brief stop at Ma’an to buy picnic supplies from the market, it was still well before 9am when we got to Wadi Rum, an avenue of mountains (wadi means valley) deep in the heart of the boundless desert.

Before my own Nissan Sunny graced these sands, TE Lawrence’s camel caravan rode through: ‘Day was still young as we rode between two great pikes of sandstone. It was tamarisk-covered: the beginning of the Valley of Rumm, they said. We looked up to the left to a long wall of rock; to the right the hills grew taller and sharper. They drew together until only two miles divided them, and then, towering, ran forward for miles. Within the walls a squadron of aeroplanes could have wheeled in formation. Our little caravan grew self-conscious and fell dead quiet, ashamed to flaunt its smallness in the presence of the stupendous hills.’

There is a modern road into the valley today, but the effect of the place is unchanged. Rum felt like the frontier, where the wilderness fringed civilisation; it was beautiful but frightening, like a rough sea.

But we weren’t there to hang about. We had only one day, and didn’t intend to waste it. Within half an hour of parking, we’d left behind the circus of camels and touting truck drivers, and were walking up the sandy slopes to the foot of the cliffs.

The rest of the day was spent wandering in the toasty heat of the sun, first through the dusty ruins of a 2,000-year-old temple, and then up into a rocky fissure to the secluded ’Ain ash-Shallaleh spring, a tranquil spot shaded by trees and fragrant ferns. The trickle of water in a parched desert and the silent views out over the sands were sweetly seductive, but we did – eventually – return to the valley floor. Late in the afternoon we joined a small group for a 4WD trip out into the red sands to watch an awesome, star-spangled sunset.

Barely 90 minutes’ drive from Rum is Petra, the most dramatic and alluring ancient site in the Middle East, perhaps the world. The city was carved out of the desert mountains 2,000 years ago by the Nabateans, a nomadic tribe who settled here and eventually controlled the trade of luxury goods between Arabia, Europe and the East. Quite simply, it’s breathtaking.

The image of its flagship building, a pillared facade of the Treasury, famously makes a scene-stealing appearance in the finale of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade as the long-lost repository of the Holy Grail. Yet, for once, the truth is more fairytale than Hollywood’s fiction: after earthquakes knocked Petra into rubble in the eighth century, it lay forgotten for centuries while knowledge of its location and importance faded.

The local Bedouin were the only people who knew of the site until Johann Burckhardt, a Swiss adventurer, stumbled upon the fabled city in 1812, and brought news of it back to the West. Since then, archaeologists have been at work uncovering the old stones; they estimate that they’ve cleared around 1% of the site so far (no sign of the grail), but that still adds up to plenty of room for weeks of exploration. By the time we’d chosen a hotel, checked in and headed down to the ticket gate, we had nine hours until dusk.

The secret of Petra’s ancient success was its location, sandwiched invisibly between two walls of virtually impenetrable mountains: without local knowledge, there was simply no clue that a city – which, at its zenith, was home to 30,000 people – even existed in this dusty landscape. Petra’s only entrance was via a tall, narrow canyon – the Siq – which wormed its way through the mountain barrier. This remains the main route in (unmissable if you’re new to Petra), but both my travel partner and I had walked it before and fancied trying a new route.

“Asalaam alaikum.” We made our greetings to the men drinking thick, aromatic coffee at the Petra Visitors’ Centre. Most returned a greeting in Arabic; several said ‘Welcome’ in English.

“Can we walk along Wadi Muthlim?” we enquired.

“No problem,” he said. “Takes two hours, maybe three.”

Fine, we thought, we have time. But then he brought up the question of water snakes. It was still some weeks away from summer and rainwater from the winter downpours was standing in rockpools all over Petra, apparently harbouring malevolent reptiles.

We weighed it up – or, rather, I did. My so-called partner wasn’t to be deterred, and was already heading out to do battle with the serpents.

The initial stages of the trek into Petra always remind me of an opening scene in a juicy episode of Doctor Who. You’re walking on a path of dust and gravel, leaving familiarity behind; high above to one side is a steep, enveloping ridge which gives an echo to the sounds of people and horses making their way to and fro. On the other side is a moonscape of bleached-out, eroded rocky domes, pockmarked with caves. Strange carvings and squared-off blocks flank the route: evidence of an alien civilisation. The path heads ominously downwards. It feels like an adventure on another planet.

We came to the Nabatean dam, which marks the entrance to the Siq. The air was thick with the smell of horses and a few tourists were heading off down the gorge. We branched off into a high-arched tunnel, also built by the Nabateans, and emerged at a narrow, high-sided valley, utterly silent but for the occasional snatch of birdsong. As we proceeded, passing another ancient dam and squeezing by a giant boulder that all but blocked the way, the valley walls constricted further, until my shoulders brushed both sides of the cliffs as I walked.

Claustrophobia, isolation and the deafening silence were making me a little edgy as we entered a high, narrow, cross valley. Its walls were smooth, eroded by flowing water, and clearly of some importance: the Nabateans had left dozens of carved niches in the walls as monuments to the dead. Their presence, and the curved horns adorning some of them, didn’t help my edginess. It was then, at a point with sheer, unclimbable sides, that a rockpool too wide to jump blocked the way. My imagination created sinister dark shapes slithering below the murky water. But there was no going back.

Without hesitation my partner turned to face one wall, put both hands onto the rock, and then adroitly walked her feet up the other side. She shuffled her way over the rockpool in this crab-like fashion and expertly dropped down on the path beyond. Thank heaven for resourceful companions. I swiftly followed suit, as if I didn’t care (although I did). On the other side, I looked back into the pool. There didn’t seem to be anything there.

There were two more rockpools en route, and we did the same at each. It was the middle of the day by the time we arrived in the centre of Petra: it had been a long walk, and a sea of snakes was still coiling around in my head but, standing before the Treasury, the sense of achievement was invigorating.

Sunday was our last full day so we bid Petra goodbye and, at a very missable junction on an unremarkable bit of road, we headed down a broken track to Dana Nature Reserve. Below the road, and invisible from it, yawns a huge cleft pointing south-west: Wadi Dana.

At its head, like an amphitheatre, is a semi-circular ridge and, on one arm of the ridge, a little cluster of old, stone cottages. This valley is the focus of Jordan’s flagship nature reserve, still the only example of truly sustainable ecotourism in the Middle East – and tragically little-known, which may explain the irrepressibly enthusiastic greeting that awaited us at the Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature’s (RSCN) guesthouse.

“Hello, hello! How are you? So pleased to see you! Welcome. Ahlan wa sahlan! Welcome to Jordan, welcome to Dana!” My hand was pumped, my back was clapped – Jihad greeted me like a long-lost brother. He bustled us into the low stone building, served us coffee and told us all about Dana as the warm, dry breeze gently blew in from the valley below.

For generations this was a farming community, but when 20th-century technology offered villagers a better life elsewhere, Dana fell into disrepair. It lay semi-abandoned until the RSCN won funding in the early 1990s to renovate many of the cottages, as well as creating a reserve and research station.

The RSCN employed the villagers to process Dana’s crops of olives, figs, grapes, fruit and nuts into luxury products such as organic jams and olive-oil soaps, and encouraged the growth of traditional crafts such as pottery and leather-making. In 1996 a small guesthouse was built, hiring locals. It’s been an amazing success, bringing prosperity to the local people while preserving the delicate environment.

Jihad twinkled with pride as he spoke. We could have talked for hours, but there was walking to be done. Under the kindly eye of Abu Yahya, one of the RSCN’s best guides, we started out on the path to Shag ar-Reesh, a high, narrow gorge that splits a group of angular crags south of Dana village.

The walk was superb but testing: it began easily enough, winding through flower-filled meadows and along quiet terraces, but as we hit the main canyon, we had to scramble up the gorge’s steep slopes. The views from the cool, breezy summit, dotted with ancient cisterns and fragrant junipers, was spectacular.

That evening, sitting on our balcony overlooking the full length of Wadi Dana, we decided it was perfectly possible to have a short break in Jordan. We’d managed to see the main sights in three wonderful, hassle-free days, and now had an easy drive back to the airport in the morning to catch our 11am flight. The only thing more incredible than this Middle Eastern long weekend was the fact that so few people do it.

Having said that, gazing at the carpet of stars overhead, with the cry of the nightjar in our ears and the inky expanse of the valley below, I wished we could stay a little longer.

When to go: In spring (late March to May) and autumn (September to November) the temperatures are warm but manageable, and the desert and hillsides are blooming with flowers. Summer is too hot for exploring, and winter is generally rainy and cold – Amman regularly gets snow.

Health and safety: Visit a travel clinic for vaccination information and, once in Jordan, be careful of the water. The sense of honour and hospitality to guests embedded deep within Arab culture means that you’re unlikely to be conned or pickpocketed. As for terrorism or civil disorder, these are more common in Britain than Jordan – the media’s focus on Middle East violence applies to Jordan’s immoderate neighbours, not to Jordan itself.