An aroma of charcoal accompanies me along the flagstone path towards my townhouse. The wooden fence has been scorched black in a traditional Japanese preservation technique that has left it with the knobbly texture of crocodile skin. The front door is heady with the smell of cedar. As I step inside, the unmistakable straw smell of tatami matting envelops me in homely warmth. Faintly beneath comes the delicate perfume of flowers from the arrangement on the chest of drawers in the hallway.

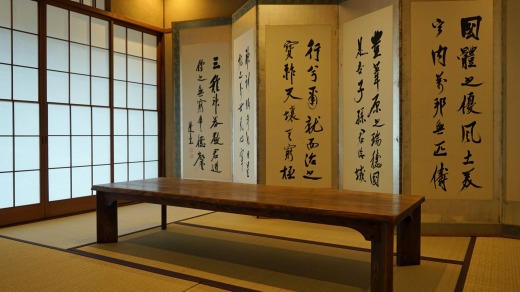

I'm staying in a traditional Kyoto townhouse known as a machiya. I expect it to be a pretty picture of hanging scrolls, antiques and clever views framed between wooden shutters, and so it is. But beyond the visual, the machiya supplies fragrance and texture too. That evening I lie in a Japanese cedar-wood bath whose aroma reminds me of forest clearings in the Kamikochi Valley. I run my hands over old beams and polished wood, and finger window blinds made of reed matting. This stay in history is a multi-sensory experience.

Kyoto is one of few Japanese cities that still has a significant number of pre-war buildings. It has an estimated 48,000 machiya, the two-storey wooden townhouses of a bygone age. Many are being lost to redevelopment, but some have been repurposed as shops and restaurants or – in an idea unusual for Japan, where travellers stay either in modern hotels or traditional inns – converted to rental accommodation. They're often still in the hands of their original owners who, while shunning the perceived discomforts of such old houses, are reluctant to sever their attachment to their family homes by selling up.

Enter folk such as Hideki Kajiura, the man behind Iori Machiya Stay. His company bought some machiya outright but offered to do others up for their owners, providing them with a small rental income by leasing them to visitors. At first, naysayers doubted tourists would stay in what they perceived to be out-dated, gloomy, inconvenient old houses. But the voices were soon silenced. Iori now has a dozen houses, and some 60 machiya across Kyoto offer tourist accommodation.

'It's all about both Japanese and western visitors wanting a taste of traditional life and adding a bit more depth to their stay,' says Kajiura. 'It's another way to experience the charms of Kyoto.'

Oku Zaimoku-cho, where I'm staying, opened a year ago and is among the most luxe in the Iori collection. It has been almost completely reconstructed, since the original building (like most machiya) had neither heating, air-conditioning nor proper plumbing. But the work has been done without compromise, using old building techniques and craftsmanship, and old materials sourced from around Kyoto.

Sliding paper doors close off the living area from the raised tatami dining room. One bedroom has a Zen-like emptiness, its futon beds neatly folded in a cupboard and only taken out at night when it's time to sleep, although the other bedroom has western-style beds.

This isn't just a museum display to a bygone lifestyle, however. Machiya took on their form as merchants' houses in the seventeenth century but have always adapted to current uses. This one is no different. I'm relieved to find a western-style sofa that saves my back from cross-legged mat sitting. That traveller's joy, a washer-dryer, is tucked into a discreet kitchen niche, though it has a baffling array of Japanese-inscribed buttons that wink and beep. Fortunately, some handy English instructions in a folder soon have my clothes a-tumbling.

Upstairs, in contrast to the Japanese-style downstairs bathroom, there's a modern shower cubicle and all-squirting, all-talking Japanese toilet with controls that would surely rival those in the cockpit of a space shuttle. One of the disconcerting cross-cultural entertainments of Japan is to sit on such a loo and dare to press a button for a wash, blow-dry or simply the most unexpected of gushings and gulpings whose purposes I've never undetermined.

This old-new fusion is quintessentially Japanese, and nothing new in Kyoto, where kimono-clad ladies pull mobile phones from their obi and raucous, light-flashing pachinko parlours are a walk away from sedate teahouses and temples.

My machiya has a basic kitchen: fridge, microwave and very welcome coffee machine that gurgles like a happy baby in the morning. The kitchen isn't really designed for cooking full meals, however. Anyway, why would I bother? Eateries are abundant and good value in Kyoto, and food halls a spectacular Babylonian display of astonishing temptations. One night, I stock up in a Daimaru department store on sushi, smoked mackerel and bento boxes and carry them home. My machiya has an outdoor dining deck right on the edge of the Kamogawa River, where I watch herons strut and locals cycle past along the towpath as I eat.

Staying in a machiya isn't just about the experience of an old house, either but an entire neighbourhood. My street meanders along a canal lined by cherry trees and has several restaurants from which the smells of wasabi and tempura waft. I plunder little shops for evening sake and breakfast dumplings. Locals pedal past, visit the nearby dentist, walk their dogs. Bundles of roses outside a shop provide me with passing perfume as I wander homeward.

www.jnto.org.au

www.pref.kyoto.jp/visitkyoto/en/

GETTING THERE

Japan Airlines flies from Melbourne and Sydney to Osaka's Kansai airport, an hour on the train from Kyoto. Phone 1300 525 287, see www.au.jal.com

STAYING THERE

Iori Machiya Stay provides a variety of sensitively renovated machiyia in premium and standard categories and varying sizes. Oku Zaimoku-cho costs between $170 and $375 per person, per night for four. Cleaning and concierge services are provided.

Phone +81 75 352 0211, see www.kyoto-machiya.com

EATING THERE

Gion Raku Raku, in one of Gion's most atmospheric streets, serves a fine kaiseki meal, or traditional multi-course menu showcasing seasonal flavours and the chef's artistry. Phone +81 75 532 0188, see www.gion-rakuraku.com