Adventure changed to trouble when I rounded the bend of a narrow road that had long ago turned to a sloppy single track of red mud.

A tempting sight leads to an exciting experience

Down in the valley below and barely visible through the mist was Sapa. I had taken my rented motorbike down a dirt road some four hours ago. I was tired, hungry and thirsty. Having Sapa in my sight was temptation with a capital T. And as the song goes, that stands for trouble.

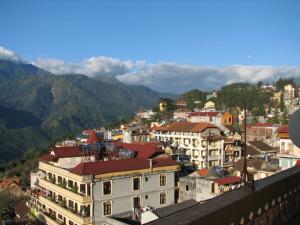

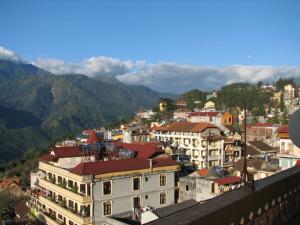

Sapa, Vietnam

Sapa, Vietnam

The town is in the most hilly/mountainous section of northern Vietnam. The trail I took hugged the side of a steep valley of terraced rice paddies and vegetable gardens. There is one paved road that runs through Sapa. On my first day, Dave, Jonna and I headed west towards Fansipan, a nearby 3,143-meter mountain. The narrow, twisty road was perfect fun on a motorcycle. Part of the experience was dodging potholes, goats, pigs, water buffalo and oncoming trucks.

I had hoped to climb Fansipan; it’s non-technical, and there’s a trail all of the way to the top. But there’s also a guard at the trailhead and you can’t hike it without having a guide. Theoretically, it’s a three-day climb, although it has been done in one. All I wanted to do was hike, even half way up, then come down. No luck unless you hire a guide for three days.

Outside Sapa

Outside Sapa

Tooling around on the bikes was solace enough. After a roadside lunch of BBQ pork and sticky rice, we headed east to find the Black Hmong Village of Ta Phin. This region is also home to the Montegards, Dzao and several other hill tribes.

Ta Phin is a village where tourists can do homestays, so Westerners are a common sight. The villagers invite you into their homes in the hope that you’ll buy their handicrafts. I gave a ride to a young man coming in from town to his house. He brought out and introduced his entire family; they asked me inside. I didn’t have any small currency dong (about $6.00 worth), and not really wanting to buy anything, I declined.

Dzao Tribeswomen

Dzao Tribeswomen

After leaving Ta Phin, I found a dirt trail that was obviously used by motos; I figured it needed to be explored. After 30 minutes of negotiating hairpin turns that snaked around sheer drops, I was in a scene out of a 1950s National Geographic magazine. I came across tiny villages in back valleys where people live a life without any noticeable modern influences (other than the occasional motorbike). Folks were plowing with water buffalo; kids only knew one word of English, hello; all were dressed in traditional clothes. Ladies were busy dyeing cloth and embroidering fabric. The mountain sides were mostly terraced; there were rice paddies and vegetable gardens everywhere.

I came to a fork and took the high road, of course. Some 20 minutes later, the trail became a footpath. After another half hour of riding, slogging, and pushing my moto up some steep inclines, through creek beds, Sapa appeared through the mist. The single track abruptly ended; became a foot path that was cut in the mountain side. When a little barrier made of stacked rocks blocked the path, I should have realized it was not meant for motorbikes.

Rice paddies

Rice paddies

With the remaining common sense that old age has left me, I discarded the bike and walked about 50 meters past the rocks. It was dicey, but doable. I would have to push the motorbike and hope that I didn’t slip off the edge, but then the trail widened after a bit. With Sapa down below, I decided to go on.

It took some 20 minutes to get through that section, as it was mostly downhill. I then left the bike and walked ahead another 50 meters and realized that I was in it, and in it big. The trail became a steep and rocky drop. A hiker would need to use hands to keep from falling. There was no way I was going to get the moto down. A retreat was my only option. But backwards was all uphill, through rocks and mud.

I’ve done a lot of walking in these last few months, but nothing too physical or aerobic. And nothing where I had to hope that my feet wouldn’t slip out from under me, and send me and a bike tumbling off of a cliff. It took an hour to muscle the bike back up to the trail. Lots of road engineering was needed to provide enough traction to the rear wheel, as I pushed the bike while giving it some gas to help it along. Mud was flying everywhere. More than several of my very best, very bad words were muttered. That isn’t the sort of trouble you want on a trip like this.

I jumped back on the moto and followed the low road – in this case, the right road. Soon, I came across a man in traditional Black Hmong purple-dyed clothing taking a break, sitting on top of a rock. He had a meter-long pipe cradled in his lap. With a dramatic mountain background, it was a perfect photo opportunity. I pulled out my camera and motioned if it would be ok to take his picture – it wasn’t. At the moment, I wished I had taken along some American cigarettes to give him and to establish some rapport, but since I didn’t have any, I shrugged my shoulders and continued on.

The remainder of the afternoon was an easy ride; there was only one section where road construction had begun, and where I had to walk the motorbike. A Hmong man and young son were pushing their bike up through the rocks as I was easing mine down. After I was safely down, I helped them get theirs to the top. Big smiles all around.

I got back to town as the mist was turning into rain, as the roads were turning to a slippery mess. I dropped my bike off at the designated corner, but the almost new Honda was covered in mud. The owner looked concerned and started to closely examine the bike. I did leave a few scratches on the plastic cowling. A crowd gathered around. Every little mark (new or not) was pointed out. The situation was getting a bit tense.

I had rented the motorbike for $4.00 for the day, and quickly offered to pay another dollar for the damage. He suggested I pay $2.00 more and that was fine with me. I was gone before the mob had any thoughts of a lynching.

There's more on Sapa in Blurry Travel.