Winner of Best Travel TV Show in the Reader Travel Awards 2014, Simon Reeve talks to Wanderlust about buying fake Somali passports, getting malaria and eating penis soup

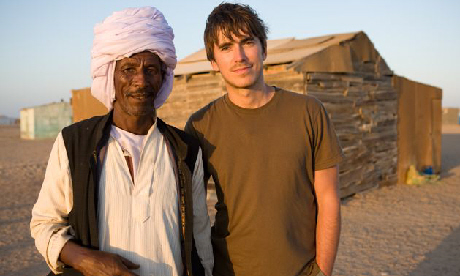

Best-selling author, adventurer and award-winning BBC documentary maker Simon Reeve is a traveller who needs little introduction. Known for his series exploring the Tropics of Capricorn and Cancer, travelling the Indian Ocean and following the world's great pilgrimage routes, he talks to Wanderlust founder Lyn Hughes about the defining moments in his career so far.

Have you always been interested in travel?

No, I can't claim I have. I wasn't stowing away on planes or inter-railing when I was a lad. I grew up in Acton and my world didn't really extent much further than west London. We used to go to Studland Bay down in Dorset twice a year but I only went abroad twice and I didn't get on a plane until I started working. I came to travel quite late and I regret that now. It's rather fun!

So what did you want to do when you were a boy?

No-one has ever said to me, “You always said you wanted to travel a lot”. When I left the education system I had no idea what I was going to do in life. I felt completely unprepared. I was on the dole for a year, I ran charity shops and bummed around quite a lot before I finally got a job.

And what was that job?

I started out working as a post boy on The Sunday Times. It was brilliant for knowing everything about the newspaper and who everybody was. I started saying to people, “If you want someone to do some research for you, I'm your man. I'm a bit keen, desperate and I don't want to go back on the dole.” They would let me help with photocopying and eventually with research and a little bit if writing. I graduated from there really.

So how did you go from there to writing your first book?

I think it was the arrogance of youth. I didn't have a mortgage or anybody depending on me. I'd started specialising in investigations and my big break at the newspaper was finding a couple of terrorists who were on the run in Britain. They were South African neo-Nazis and I tracked them down to where they were hiding out in Lincolnshire. It was all very surreal. The whole subject area started to fascinate me and I came to specialise in terrorism. In 1993 there was the first bombing of the World Trade Centre in New York. I started investigating it for the newspaper. After they got a bit bored with me suggesting articles about it I thought, “There's a book in this. There's a deeper story to be told”. I left the paper and had this bizarre five years where I was researching what we now call al-Qaeda and having lots of strange experiences along the way.

Where were you when 9/11 happened?

I was my flat in west London when my brother told me to turn on the TV. The first Tower had just been hit. The conclusion of my book had been that there was going to be an apocalyptic attack by this group. It came out in 1998 but it languished at the back of bookshelves. Nobody was interested. It had started out as an investigation of the first World Trade Centre attack so I knew a lot of people in the Towers. I was actually physically sick; it was hugely upsetting. My phone starting ringing before the second plane hit. It didn't stop for about a year and a half.

How did you move from covering terrorism to getting into travel?

When 9/11 happened I'd written the only book on Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda. I was thrust onto the telly, mainly in America, to explain why and how this had all happened. Then I started having meetings with the BBC about what I could do. They had some mad ideas initially: “Can we make a series where you infiltrate al-Qaeda?” I politely said I didn't think that was a good idea. Then we talked about programmes set in places we felt we didn't know enough about.

My first series was called Meet the Stans and it was about the countries of Central Asia; Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan (Turkmenistan wouldn't let us in unfortunately). It was my first experience of TV but I loved it from the first day we started filming. It was an adventure and I was discovering something new every single hour of the day. I can't quite believe I'm still here doing it ten years later.

How does it work when you go away with a crew? Do you drive what's going to happen or has it all been set up for you?

I'm involved at every stage and, with most of the things I've done, I come up with the initial idea. But I don't get to stamp my feet and insist that I be allowed to do things. It's a team process and the best argument wins. We want to be fair and truthful about the country we're visiting and we have to think about the cost of course. The biggest thing we have to consider is whether enough people are going to watch it to justify the expense. The Urals? Probably not. Australia? Oh yes.

Your series on Australia just won Wanderlust readers' Top TV Show, but who would you have voted for?

I’ve always loved Michael Palin’s shows. Around the World in 80 Days was quite inspiring; it wasn’t patronising in the way that a lot of BBC travel programmes had been in the past towards ‘these strange foreign people’ – it was much more on their level. I suppose I tried to learn from his style and incorporate it into mine.

Of the series you've done so far which have you enjoyed the most?

I've loved all of them but I'd say a series called Holidays in the Danger Zone: Places That Don't Exist. It was quite a rough and ready series but it was a genuine adventure to countries that aren't officially countries. There are a lot of these places; Transnistria, Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Adjaria, Taiwan. Roughly 250 to 300 million people around the world live in unrecognised country or consider themselves an unrepresented people. Often these places don't even appear on a map. You look at a map of the world and you see Somalia for example. What you don't see is that in northern Somalia there is a county called Somaliland.

In Somalia we were driven around in a pick-up truck with an anti-aircraft gun mounted on the back with a dozen heavily armed local mercenaries to look after us. I was even able to go and buy a diplomatic Somali passport with my own name and photo from a bloke called Mr Big Beard in Mogadishu market: yet it does have a seat in the United Nations. It is recognised as a functioning country. Then we flew from there to Somaliland which has strong historical connections with Britain, functioning democracy, women in parliament, traffic lights, uniformed police officers and a minister for tourism. But it isn't recognised as a country by any other state on the planet. It is a disgrace!

Somaliland is an amazing place, one of my favourite countries in the world actually. The people have build a country from the ashes of war with very little help from the outside world. Travellers are starting to discover it; in the time I’ve been going there, it’s gradually changing. Maybe more people will go there on holiday – what an amazing thought that is!

You've been in some difficult situations and even dodged a few bullets but your programmes don't seem to be about adrenaline. They're more about you trying to immerse yourself and get under the skin of a place. Would you agree?

Trying to, yes. From the outset the idea of the programmes was to show issues. Collectively as travellers we're interested in that. We don't just want to go and sit by a swimming pool and top up our tan. Learning about a country is part of it. As is eating penis soup!

Is there anything we can do, as travellers, to help address the issues that your programmes raise?

Everything we do has an impact and I think it would be crazy of us not to recognise that. How we spend our money can have a profound impact around the world. We can be careful not to spend our money in a hotel that's owned by the local dictator's son, for example. Be a bit of a pain. Ask questions when you're booking or ask the tour operator. Force them to check where the money is going. Is anything going back to local people?

What about environmental issues?

By going to national parks we're contributing to their upkeep and protecting the endangered flora and the fauna that exist there. It's important to remember that a lot of the rangers working there used to be poachers. You are preventing them from poaching by putting your money into those places. Feel virtuous about that. If you weren't going there these places would be levelled and turned into palm oil plantations or fished to annihilation.

I'm not saying there isn't a question of the sustainability of life on earth. I have a very pessimistic outlook on that. I haven't seen an example around the world where they've really got the balance right, where poor people have been lifted out of their poverty to a level that's anything approaching the luxury that we enjoy while still protecting life on Planet Earth. It's even harder to do it without preaching at them. We chopped our forest and created the conditions that led to the industrial revolution. That's why we've got everything that we see around us now. If you're poor in Madagascar, for instance, you might quite like a bit of that. We might extol the virtues of the indigenous way of life but three of their children will die before they reach four. They live difficult lives. These are such profound questions. It would take multiple TV series to discuss them properly.

What's the worst experience you've had on your travels?

Getting malaria, by quite a long way. I might have picked it up while travelling down the Amazon before flying out to west Africa. I was heading into the Congo and then I woke up one morning vomiting blood with a temperature just a shade off brain damage. I didn't think I was going to make it but, as a white, British, BBC TV presenter, I was able to get treatment. Obviously that's a luxury not everyone on the continent has. I've never felt quite the same since but I did eventually recover.

There have been other moments where I've encountered something or someone and it has upset me to the degree that I still occasionally cry about it after a few too many whiskies.

Our readers chose Mongolia as their Top Emerging Destination. Which country would you choose?

It surprises me that more people aren’t going to remoter parts of, say, Laos, Paraguay or Mozambique. They’re places where you can have a particularly memorable experience.

Is there anywhere you haven't been to that you'd love to visit?

I've been to almost all of the former Soviet Republics but I haven't been to Russia. I would love to that properly. I have an endless bucket list of places I'd like to go. It can be tempting to try to tick them off but you can also go to the same country a dozen times and have different experiences.

Tell us about your next series.

I'm filming a series called Sacred Rivers. We've just been following the Ganges through northern India. I do have those moments where I think, “I'm from Acton. I've just been following Ganges!” I'm going off in a few weeks to travel the Nile and then we're travelling the Yangtze as well. Later in the year where we'll be travelling around the Caribbean visiting the islands but also the mainland coastline. We get to explore the crime gangs and the drugs trade in Central America: the dark side as well as the light side. Personally I find that more interesting. It does result in bizarre situations though. When we were filming Australia for instance, one day I was with a vet rescuing injured koalas and the next day I was with the fearsome members of the Finks biker gang! You do get those extremes but I love that. That's what life is about.