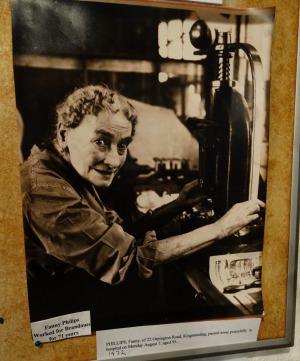

A black and white photograph pinned to a corkboard on the wall of Birmingham's Pen Museum shows one Fanny Philips sitting at a manual nib-making machine. On an average day, a woman such as Fanny would have stamped out something like 18,000 steel pen nibs – work that put Fanny at the centre of a global trade that changed the world.

It was through the hard work of women such as her that Birmingham, in the 19th century, became the centre of the world pen trade. It's said that, during this time, 75 per cent of everything written in the world was done using a Birmingham pen.

Before the invention of the first steel dip pen in 1780 the most popular means of writing for more than 1000 years had been the quill. But they took time to prepare, didn't last long and needed frequent recutting to keep the tip sharp – hence, the "pen knife".

Steel pens, on the other hand, were easy to use, lasted a long time and, once Fanny and her ilk got into the swing of mass production, reduced the cost of writing and helped spread literacy. Birmingham, quite literally, wrote itself into the history books.

Fanny Philips, by the way, retired in 1961 after working for the C. Brandauer & Co pen company for 71 years. At her retirement she was given a television and a pension of £3 a week. She died in 1972, aged 95.

In 2011 the Brandauer company celebrated its 150th birthday and in its official history it recorded both Fanny Philips' retirement and the fact that one George Wells, who had set up a pen-making business in Birmingham in 1836, was by 1848 employing 500 people and producing 262 million pens a year.

"Birmingham," it says, "was now well on the way to gaining another title as 'The Pen Shop of the World', with many more steel pen manufacturers concentrated in just a few square miles than the rest of the world put together."

Today, those few square kilometres are getting a new lease of life as the increasingly sought-after Jewellery Quarter, a conservation area full of listed Georgian buildings, jewellery businesses, funky shops, and quirky bars and restaurants.

And tucked away in one of those streets is the unassuming Pen Museum, which opened in an old pen factory building in 2001 and stands as a discreet testament to the days when Birmingham ruled the writing world.

Free to enter (though a gold coin donation is welcome) and staffed by volunteers, the museum is a treasure trove of historical writing implements and memorabilia (the collection is said to contain one million nibs). Old pens and nibs are lined up like soldiers on parade, neatly under glass or framed on walls where old advertisements spruik particular nib types: "They come as a boon and a blessing to men, the Pickwick, the Owl and the Waverley pen".

There are also several of the manual machines used by Fanny Philips and her colleagues where, with help from volunteers such as Rob Stanyard, The Nib Man, you can stamp out and create your own nib.

Past this first room, another larger space out the back has more of the collection, including displays of old inkwells, nibs and pens that are more objets d'art than utilitarian writing implements. You can, for instance, buy a Queen Elizabeth II diamond jubilee commemorative pierced nib, featuring the Queen's face, for a mere £20. There's also an area where they run regular calligraphy classes and talks.

Most disconcerting of all, though, is the collection bequeathed to the museum by a Dennis Burton after his death in 2013. Across several walls off to one side of the museum, pinned up side by side with little space between them, are the thousands of ballpoint pens that Mr Burton collected during his lifetime.

From mere quotidian biros to novelty pens shaped like bottles of Budweiser, Guinness and Heinz tomato ketchup, it's a massive assemblage of the very thing that sounded the death knell of the Birmingham steel pen industry.

The museum was recently awarded £19,500 in Heritage Lottery Fund money, after which Reyahn King, head of HLF West Midlands, said: "The Pen Museum showcases a fascinating aspect of Birmingham's industrial history and it is important to support this small organisation to continue telling the story that otherwise could be overlooked."

And it's easily done, given that Paul Sabapathy, Lord Lieutenant of West Midlands, said this year that "despite being an adopted Brummie of nearly 50 years standing, I only recently discovered the wonderful treasure that is the Pen Museum".

www.visitbirmingham.com

The Pen Museum, The Argent Centre, 60 Frederick Street, Hockley, www.penroom.co.uk

Opening hours: Mon-Sat: 11am-4pm; Sun: 1pm-4pm

From Birmingham city centre the 101 bus stops in Frederick Street outside the museum.

British Airways, Qantas, Singapore Airlines, Emirates and Cathay Pacific operate frequent flights between Sydney and Melbourne and London. Birmingham Airport is serviced by many low-cost carriers.

Birmingham's New Street Station has frequent rail services to London's Euston station and National Express coaches connect the city (at Digbeth Coach Station, just a few minutes from the city centre) to London Victoria station, with links to Heathrow, Gatwick, East Midlands, Stansted and Luton. See www.visitbirmingham.com/travel

The writer was a guest of VisitEngland and British Airways.