How to read trailblazing signs in the USA

If you're hiking in North America, you'll have to learn a whole new language: trailblazing. Here, you'll find the basics - and some handy insider tips...

Trailblazing (or 'waymarking' as it's known in the UK) is the technique of marking a path by means of a cryptic-looking sign. Just as Hansel and Gretel left a trail of breadcrumbs to mark their way home, pioneers in the 1800s recorded their routes with notches carved into trees. The practice lives on today.

How did it start?

The pioneers' markings were the first steps of recording routes through untamed nature. As people began to settle and spread around America, they began to make paths though the surrounding forest and mountains. In 1910, the Long Trails route in the Green Mountains in Vermont was created: the first ever route to be established in the USA, followed by the Appalachian Trail (1920s) and the Pacific Crest Trail (1930s).

In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the National Trails System Act with the aim of promoting "the preservation of, public access to, travel within, and enjoyment and appreciation of the open-air, outdoor areas and historic resources of the Nation." The act currently acknowledges four types of routes: National Scenic Trails, National Recreation Trails, National Historic Trails and connecting-and-side trails.

What do I look out for?

There is no wholly standard system for trailblazing signs, but the majority of signs are made by reflective pins or tacks, coloured poles, coloured tape flags (these are usually used to mark a temporary or unofficial route, or one that is still under construction), cairns, and paint, which is the most commonly used medium.

The tradition of carving notches into trees is no longer used (as it harms the tree) and neither is the Native Amerindian system of leaving 'trail trees', by which a rock is tied to a sapling to weigh it down, forcing it to grow in an awkward position.

In the U.S, there are 5 main kinds of signs that you'll see:

1. Identifier signs – These are used at trailheads to indicate who the trail is for (hikers, snow-shoers, cyclers, equestrians, skiers, motorised vehicles) and are usually square-shaped with a symbol of the trail type e.g. a bicycle or a horse. This also includes the signs belonging to the National Track Difficulty Rating System*, which are based on the type of terrain that you'll encounter on the route. It takes into consideration the gradient or slope of the land, as well as the technical ability that you'll need to successfully complete the trail. A green circle indicates the easiest trail, a blue square for medium difficulty, and a black diamond for advanced difficulty.

2. Regulatory signs – such as a stop or speed limit sign.

3. Warning signs – used for indicating danger. Words like CAUTION or JUNCTION AHEAD are usually written in black on a yellow background on a diamond-shaped sign.

4. Information signs – these are used to indicate location, direction or distance (white text on brown wood).

5. Reassurance signs – Used to assure users that they're on the right route, also to indicate direction or occasionally, caution. There are different signs for motorised or non-motorised trails*.

In addition, most famous or major trails have their own emblem, such as the Pacific Crest Trail or the Appalachian Trail.

Paint blazes

Stripes in the shape of vertical-standing rectangles are the most common form of blazing in the US, and are usually found painted on trees or rocks along a trail. They're used not only for direction but to reassure people of the trail, as well as to alert users to imminent turns or parts of the trail that are potentially confusing, like open roads, lesser-used paths, and rocky areas. They can also indicate the start or end of a trail.

Different blazes are used for different user groups (equestrian, ATVs, snowmobiles, hikers), with motorised trails using not paint but reflective diamond-shaped signs. Paint is the preferred method of marking non-motorised trails and usually indicate user group by colour (eg. a light blue tends to be used for skiers).

Do your research into the area beforehand as there's no set list of which colour indicates what – colours can also indicate the name of the trail you're on (eg. white is typically used on the Appalachian Trail) as well as the direction and/or the length of the trail (eg. the primary trails in Catskill Park (New York) are either red (if they're heading from west to east) or blue (if they're heading from north to south), with shorter connector or spur trails painted yellow).

When two or more trails run concurrently, two things can happen: either a single blaze that combines both colours is used, or the blaze belonging to the more popular or heavily trafficked route dominates (such as in the case of where the Long Trail in Southern Vermont meets the Appalachian Trail – they both use the AT's signature white blazes to mark that part of the route).

When using paint to mark trails, the system of offset blazes is most frequently used. It was invented by Bob Fuller, a volunteer for the New York-New Jersey Trail Conference, who devised the system in 1969. Blazes are usually painted using either latex or oil based boundary-marking ink. They usually need to be repainted every 2-3 years due to tree growth and weathering.

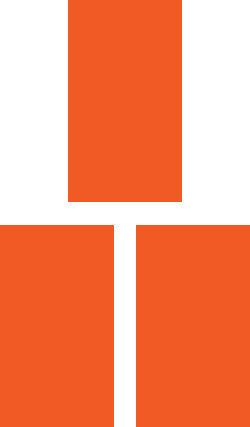

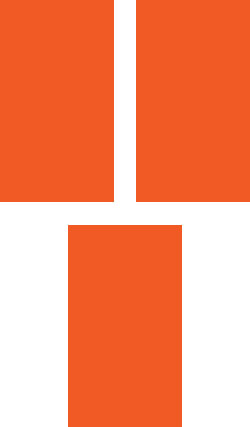

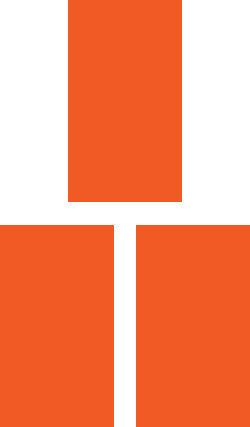

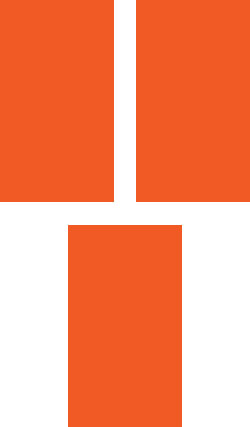

The basic blaze system can be understood as follows:

1. Continue straight

2. Start of trail

3. End of trail

4. Left turn

5. Right turn

6. Spur leading to a different trail

7. Caution (this can also be used to indicate a turn or to go straight where a turn may seem to be the case)

8. Black border – blazes are painted with a black border on backgrounds that blend with the colour of the paint

Variations: On occasion, triangular blazes also indicate either a startpoint (point upwards) or an endpoint (point downwards). You may also find rectangular blazes which are painted at an angle that forms an 'L' shape, used to signify a bend or turning, and the angle between the two blazes refers to the degree and direction of the turn.

Cairns

Apart from paint blazes, cairns are often used to mark trails in vast open areas bare of trees, areas of a higher altitude (such as those above treeline), and to identify the parts of a route which are prone to snow, fog, or other forms of precipitation that may obscure less obvious trail markers. These tower-like, man-made structures are built from broken stone, and are usually found in the Arctic region of North America, particularly Alaska and Greenland.

The height of these structures varies considerably, with smaller ones consisting of merely 3 or 4 stones piled on top of each other, to bigger, more complex constructions reaching a few metres high. A 'duck' is a small cairn built with a rock (or 'beak') on the top that points to a certain direction; these are more commonly found in the west.

Occasionally cairns are built by trail users for recreational or spiritual purposes; park rangers discourage such behaviour and dismantle these types of cairns, as they interfere with navigation on the route.

Learn your hiking lingo

Loop trail – A trail that brings you back to the place where you started without walking the same way (i.e. in a circle or loop).

Out-and-back/In-and-Out trail – Routes that start at a trailhead, lead to a particular destination/monument/place of interest, at lead back via the same route to the same starting-point.

Spur trail – A short trail that forms a branch from a longer, more important route, or a minor trail that connects two major trails.

Switchback/Hairpin bend – Named because of its similarity to a hairpin, these are sharp bends on a path or road which have an extremely acute inner angle, making it necessary for a vehicle to swerve at close to a 180° in order to continue on the road. The term 'Dead Man's Curve' is also commonly used in the United States.

Thru-hiking – Hiking a complete trail from one end to the other.

Trailhead – The point at which a trail begins, usually marked by a sign.

All illustrations by Natasha Singh.

When two or more trails run concurrently, two things can happen: either a single blaze that combines both colours is used, or the blaze belonging to the more popular or heavily trafficked route dominates (such as in the case of where the Long Trail in Southern Vermont meets the Appalachian Trail – they both use the AT's signature white blazes to mark that part of the route).

When two or more trails run concurrently, two things can happen: either a single blaze that combines both colours is used, or the blaze belonging to the more popular or heavily trafficked route dominates (such as in the case of where the Long Trail in Southern Vermont meets the Appalachian Trail – they both use the AT's signature white blazes to mark that part of the route). 1. Continue straight

1. Continue straight  2. Start of trail

2. Start of trail  3. End of trail

3. End of trail  4. Left turn

4. Left turn  5. Right turn

5. Right turn  6. Spur leading to a different trail

6. Spur leading to a different trail  7. Caution (this can also be used to indicate a turn or to go straight where a turn may seem to be the case)

7. Caution (this can also be used to indicate a turn or to go straight where a turn may seem to be the case)  8. Black border – blazes are painted with a black border on backgrounds that blend with the colour of the paint

8. Black border – blazes are painted with a black border on backgrounds that blend with the colour of the paint