...Or maybe not. Many theories have been purported about the Nazca Lines – extraterrestrial airfield being just one – but just what is the meaning of Peru’s ancient desert etchings?

As the small plane banked steeply, I looked down on the bug-eyed figure of a man pointing enigmatically at the sky. It could have been a cartoon character from a contemporary TV show but the 35m-high geoglyph, known as the Astronaut, was created around 2,000 years ago and, after more than 80 years of research, we can still only guess why.

Around 400km south of Lima, the Nazca Lines are huge, intricate drawings etched on to the barren landscape of Peru’s coastal desert. They have perplexed archaeologists, anthropologists, scientists and enthusiastic amateurs since they were discovered in the 1920s. Over the years they’ve been identified as everything from an astrological calendar to sacred pathways, a map of water sources to alien landing strips, but their exact purpose and meaning still remain unknown.

It’s believed that the Nazca people, who predate the Incas by as much as 2,000 years, created the lines. Skilled agriculturists, they settled along fertile river valleys fed by water from the Andes around 200 BC. Here, they built complex irrigation systems and aqueducts, created sophisticated pottery and elaborate textiles and, despite the harsh conditions, flourished for eight centuries.

During that time they treated the desert as an enormous canvas. Using their hands and rudimentary wooden tools they dug shallow trenches, removing the dark stones and top soil to reveal the lighter coloured earth underneath, creating literally hundreds of enormous lines, geometric shapes and recognisable zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figures.

That they’re still visible today is thanks to Nazca’s extreme environment. It’s one of the driest places on the planet, with as little as 2mm of rain a year. The sun-hardened surface has set the stones in the soil, a rich mixture of clay and gypsum; the harsh wind known as the paracas (‘sand rain’ in Quechua) is deflected by the heat rising from the stones, minimising erosion and helping to preserve them intact.

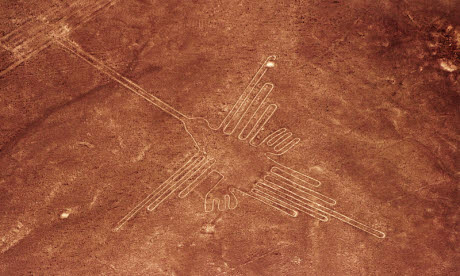

The lines are spread across a 500 sq km desert plateau and their sheer size – some of the largest are 200m across – means that they can only be properly seen from the air. As I flew north from the city of Nazca, over the vast, arid pampa of Palpa, flanked by the long spine of the Andean foothills, stark white lines began to appear. Straight at first, they criss-crossed the ochre and rust-red earth of the desert floor. They soon began to form simple geometric shapes – rectangles, triangles, trapeziums – until I caught sight of the first of the most legendary lines, the menagerie of elaborate birds and animals.

“Coming up on your left, the Ballena,” said the voice in my headphones over the roar of the engine. I scanned the ground trying to pick out the faint form of a killer whale from the muddle. The plane tipped and dipped, left and right.

“Perro [dog],” the voice said, moments later, and then, “Mono”, as the distinctive Nazca monkey with its spiral tail came into view. I was enthralled by the figures – the elegant Colibri, or hummingbird, and what was clearly a gigantic spider. I twisted from side to side as the lines appeared and disappeared in quick succession, undeterred by the surges of thermal turbulence that had several of my fellow passengers reaching for their sick bags.

How were the Nazca Lines created so precisely? Some continue for kilometres on end. And why? Even their dates are uncertain, estimated from shards of pottery found nearby.

Peruvian archaeologist Toribio Mejía Xesspe rediscovered the lines in 1926 but one of the first to comprehensively study them was American geologist Paul Kosok. In 1939 Kosok was conducting studies on ancient irrigation systems when a pilot told him about the lines. He soon realised that they were too shallow to carry water, so must have another purpose; he assumed it was astronomical after seeing the sun setting exactly over the end of one of the long, single lines at the winter solstice. He christened Nazca ‘the largest astronomy book in the world’.

Later, Kosok’s assistant, Maria Reiche, a German-born teacher and mathematician, found the same effect occurred on the summer solstice. She began to map the lines and discovered 18 different kinds of animals and birds. After Kosok left Peru in the 1940s, Reiche remained, dedicating her life to unravelling the mystery.

Her former home near Nazca, where she’s buried, is now a small museum, filled with her yellowing maps, blueprints, measuring tape and rolls of papers. There are photographs of her perched on top of a ladder in the middle of the desert, squinting in the bright sunlight to examine the lines; she even persuaded the Peruvian Air Force to help her make aerial photographic surveys.

Dubbed ‘the Lady of the Lines’, she also brought them to the world’s attention and played a vitally important role in their protection and conservation, educating both the public and the Peruvian government about their importance. She paid for private security to prevent them from further damage and convinced the government to limit access to the area. In 1994, four years before her death, the lines were finally declared a Unesco World Heritage Site – though not in time to save the Lizard, which was sliced in two by the Pan-American Highway.

Reiche believed the lines were built with sophisticated mathematical precision. However, in 1968 the English astronomer Gerald Hawkins effectively disproved her theory of astronomical alignment. He specialised in the field of archaeoastronomy and, using the same techniques he applied at Stonehenge, found that the lines he studied didn’t correspond to any celestial bodies.

The same year, perhaps the most implausible theory on the lines came from Swiss author, Erich von Daniken, who suggested in his book, Chariots of the Gods, that they were the runways of an ancient airfield used by extraterrestrial spacecraft. Other researchers believe that the lines are a precursor of the Inca ceques (sacred pathways) that radiate from Cusco, or a giant map pinpointing underground water supplies.

Because the lines are best seen from above, there are those who suspected that the Nazca were capable of flight long before Leonardo da Vinci sketched his flying machines. Pottery remains depict what could have been a kite or balloon, so enterprising researchers created a balloon out of materials that would have been available to the Nazca; after several attempts, it was airborne for less than 15 minutes.

While most people only view the Nazca Lines from the air, to really grasp their scale and the harsh nature of the terrain, you need to see them at close quarters. Before 1994, you could drive up to them in your car but now the closest you can get is the observation tower that Reiche helped to sponsor.

Climbing the rickety metal staircase, I could see how the Pan-American Highway had split the barren landscape in half, disappearing into the horizon en route to Chile. The odd lorry rumbled by, but then all was silent save for the whistling wind.

The flat, rock-covered plain stretched as far as my eyes could see, only broken up by the occasional dune and the pale lines that, from that tower, appeared as wide as a pathway. I looked out in awe over the upside-down figure of the Tree – perhaps the tree of life, or more likely the huarango tree that used to flourish here; with the longest roots of any tree in the world it could reach the deepest water and would bring it back to the surface for other plants.

Next to it is the figure known as the Hands, one with four fingers, the other with five. According to Josué Lancho Rojas, it’s more likely a frog or a toad. Josué is a historian and Nazca expert. At 68, he’s spent years studying the lines, working closely with archaeologists such as the Italian, Giuseppe Orefici, whose finds can be seen in the small but fascinating Museo Didáctico Antonini in Nazca.

Simply put, Josué believes that the area is a giant open-air temple, designed for pilgrimage and worship. “You have to imagine the world of 2,000 years ago,” he told me. “The Nazca people had simple lives but they were extremely religious. Everyone believed, not in a god they couldn’t see, but in the elemental world around them – the sun, moon, stars, wind and water.”

Nazca, he told me, came from nanasca, a Quechua word that means pain and suffering – probably coined due to the long periods of drought the people suffered. They were dependent on nature for their survival – water, or lack of it, ruled their lives. “From January to March there was water in the river, from April to December they would pray for rain.”

Josué believes that each clan had a minor god, whose figure was represented on the pampa. Around 80% of the figures consist of just one line; he thinks that these were designed to be walked on, and that the straight lines were roads that would lead the people to their figures.

Their figures were from the world around them: so not an astronaut (a name given by one of the first pilots to fly over it) but a shaman; not a condor but a long-tailed mockingbird. I asked about the monkey and the parrot, both from the Amazon. “They would have traded with the jungle peoples,” Josué explained.

On important dates the Nazca would carry out ceremonies on the lines as an offering to the gods in the sky to secure a flow of water from the Andes. “Around October, they would check the cloud formations in the mountains and, if by the December solstice there was no rain, there would be human sacrifices to appease the gods and ensure their good will,” Josué told me. This theory is borne out by the mummified, severed heads in the Ica Regional Museum. They have hair (again, thanks to the preserving desert climate) and a rope threaded though a hole in the skull, presumably to help people carry them.

Josué doesn’t believe they were exceptional mathematicians and astronomers, although that theory appeals to nationalistic pride; they were, he reckons, just a society in which everyone developed a skill and had a part to play. Their knowledge of weaving, for example, helped them to translate the images on to the vast canvas of the pampa. And as for the alien theory, he simply rolled his eyes.

In a flurry of dust, I crunched across the stony, unforgiving ground, the setting sun casting my shadow over the parched earth. From my vantage point on top of a small hill by the highway, lines and geometric markings were spread out in all their elemental glory. It became clear how inextricably linked they are – how linked the Nazca were – to this austere environment.

New lines are being found, new theories abound and new technological research is sure to increase our knowledge. But looking out over the ambiguous markings, it was thrilling to think that, in this world of information overload, there are still things that may never be completely understood.