In a landscape dominated by high-tech GPS, Keith Austin champions the utility and beauty of an old-fashioned map.

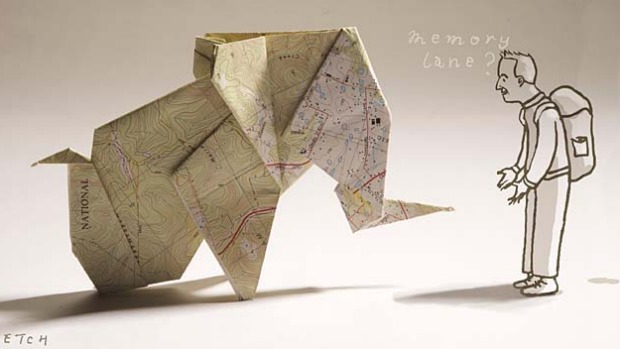

I love maps. Not Google Maps. I like Google Maps but I love maps, proper maps: maps made of paper and almost impossible to fold up again without a black belt in origami. I have one here next to me now, for research - an English Ordnance Survey map, 95 centimetres wide and 120 centimetres long, printed on both sides.

I love its myriad squiggly lines, the different shades of green, the red main roads, the dotted footpaths and the names you can find if you look hard enough: Fishes and Peggy Hill, Cat Gallows Wood, Little Kittycaul, Great Kittycaul, Hell Syke Bridge and the unfortunately named Buttock.

It's primaeval, I think, this obsession with maps. The former product manager of Google Maps, Jess Lee, blogged: "Humans have been making maps since the Stone Age. In fact, map-making predates written language by several millennia."

Of course, these days, thanks to Lee and her colleagues, we have maps up the wazoo. Google Maps, GPS, sophisticated cameras that transmit digital data from outer space, geographic information systems, Google Earth 3D maps, remote sensing, you name it.

Cartography is hard-wired into us. "I'll draw you a map," would have been one of the first sentences ever grunted, I'm sure. Could this be why we love stories involving treasure maps? These days, actual treasure maps are harder to find but the gold in a good map is still there, in the details.

About 25 years ago, a friend and I went camping in Scotland. We took backpacks, a tent and an Ordnance Survey map. The tent, the backpacks and the legs that carried them uphill and down dale are long gone - but I still have that map.

It's a little torn and tattered, showing "Loch Alsh, Glen Shiel & surrounding area", but that Landranger 33 map brings back memories in a way no Google Map could. The scale is two centimetres to one kilometre, with heights shown in numbered contours of 10-metre intervals; the closer together the little wavy brown lines, the steeper the climb.

There is the little black line that denotes the railway that brought us to the Kyle of Lochalsh village late one night, after a journey from London via Inverness.

The line is there on the Kyle of Lochalsh Google Map but the context is missing. Yes, the streets are all named but the surrounding hills are bland, blank spaces; it feels lifeless. On my OS map, there's a sense of the topography - the reality - of the place, thanks to the brown whorls of the contour lines, the fingerprints of nature.

You can see as the railway leaves the village, it goes through two cuttings and then, further north, the view out of the right-hand, east-facing window will be obscured by an embankment.

This goes to the very heart of the joy of these maps - the attention to detail that includes tiny icons depicting lighthouses (in use and disused), high-water marks, good viewpoints, campsites, youth hostels, public rights of way, bridle paths, quarries, electricity lines and pylons, woods (coniferous, non-coniferous and mixed), orchards, parks, radio masts, windmills (with or without sails), antiquities (Roman and non-Roman), battlefields, churches/chapels (with tower, with spire, without tower or spire), National Trust land, Forestry Commission land, post offices, public houses, town halls, milestones, refuse tips and the positions of various tumuli.

They're also, as they say these days, user-friendly. You need nothing other than your eyes. The icons are simple and easily decipherable. And a map never runs out of batteries.

There are also, on this map, the three little X's that I added myself, to denote where we stopped for lunch on the first day (at a pub in the hamlet of Dornie) and where we visited stunning Eilean Donan Castle. The third X marks where we camped that first night, off the road and up the steep hillside above Loch Duich.

If I squint hard enough, I'm sure I can see the little blue line that is the stream we used that night to cook our pasta and brush our teeth. Which, in turn, brings back memories of drinking a few beers as the sun set over one of the most splendid landscapes in the world.

The index on the OS map mentioned earlier - the Explorer OL41 showing the Forest of Bowland & Ribblesdale - runs the length of the 120-centimetre side and even shows where you'll find loose rock, boulders, outcrop and scree. Mud and sand are different colours. I was there a few years ago to explore Lancashire's Pendle Hill, a great flat-topped upturned row boat of a thing that, at 558 metres high (and 11 kilometres long), misses being classified as a mountain by 52 metres. As I wrote at the time, after consultation with the OS map, "Hmm, bugger coming at it from the east!"

Again, the memories come rushing back. How I avoided the steep eastern ascent by starting from the village of Barley, how I skirted the Lower and Upper Ogden reservoirs, how I laughed to myself at the signs to Buttock and made my way to the summit by the easier Boar Clough route. And how, with an OS map in hand, it really is impossible to get lost.

So you can keep your Google Maps and your GPS, I'm sticking with the real thing. If I can get this Forest of Bowland map refolded, that is. Wish me luck, I'm going in.